Coding for a New House

I don’t want to read about it, just take me to your super cool interactive map.

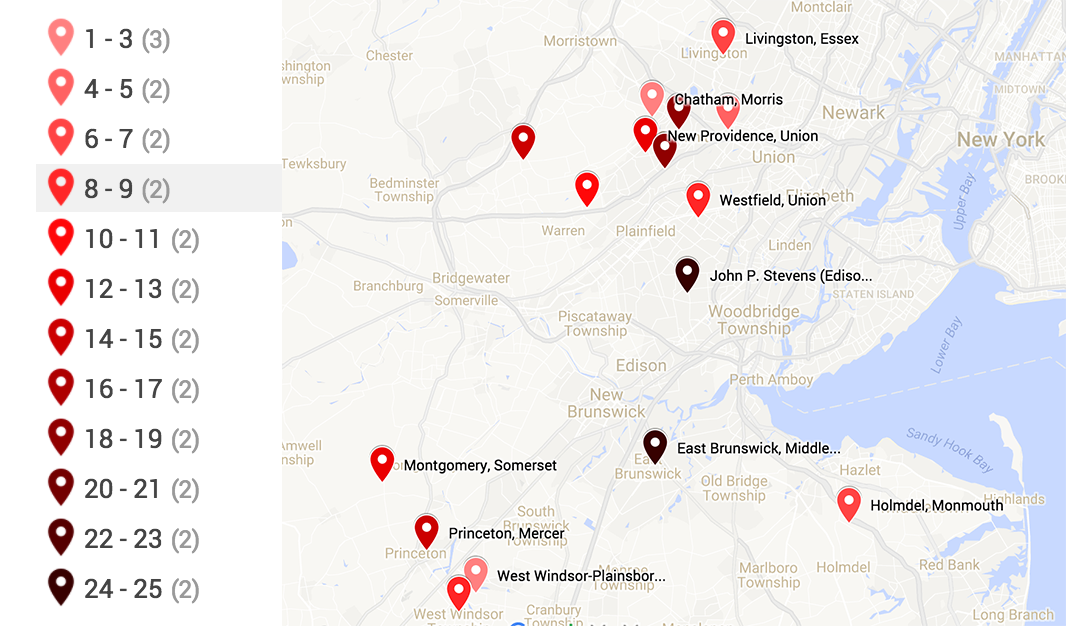

We are moving to the greater New York City area this summer where Tim joins the leadership team of Colgate-Palmolive. As tempting as it is to spend all our time on Trulia, Estately or Zillow looking at specific houses, we knew that our focus was best spent on understanding the different areas and the trades they presented. I’m an analyst at heart, and always try to do the analysis at the right level of detail. At this stage, this means a map that incorporates (in order) schools, commute times, and lifestyle options. As an advisor to spatial.ai, Tim’s been inspired to create insightful mashups. Maps are pretty much the most excellent example of useful data where one can quickly do analysis without any voicetrack. The right map can serve as a common medium for discussion with friends, realtors and our own understanding as we try to hone in on the right area. With a good contextualized spatial understanding, we can be ready to make the quick decisions that house-hunting presents.

This is why a large number of sites display helpful data geared towards house-hunters. As we started looking at different map-based real estate search engines online, we found different merits to each one but no site gave us the commute, school information and the lifestyle options we care about in one interface. Estately was the most promising. The product side was clearly driven by developers with clean url lookups and clever metrics like walkability. Trulia is the most full featured with some really cool features, like price heatmaps that would be useful if they didn’t have so many blank regions. I enjoy Trulia the most, but it doesn’t have the latest listings.

Zillow has an awesome api but legally can’t provide anything that can be called "bulk data". Redfin’s killer feature is the ability to search by school district. This is pretty much critical, since the school district doesn’t often match the town name and we started falling in love with houses online that we had to give up once we found out it wasn’t in a school district we were ok with.

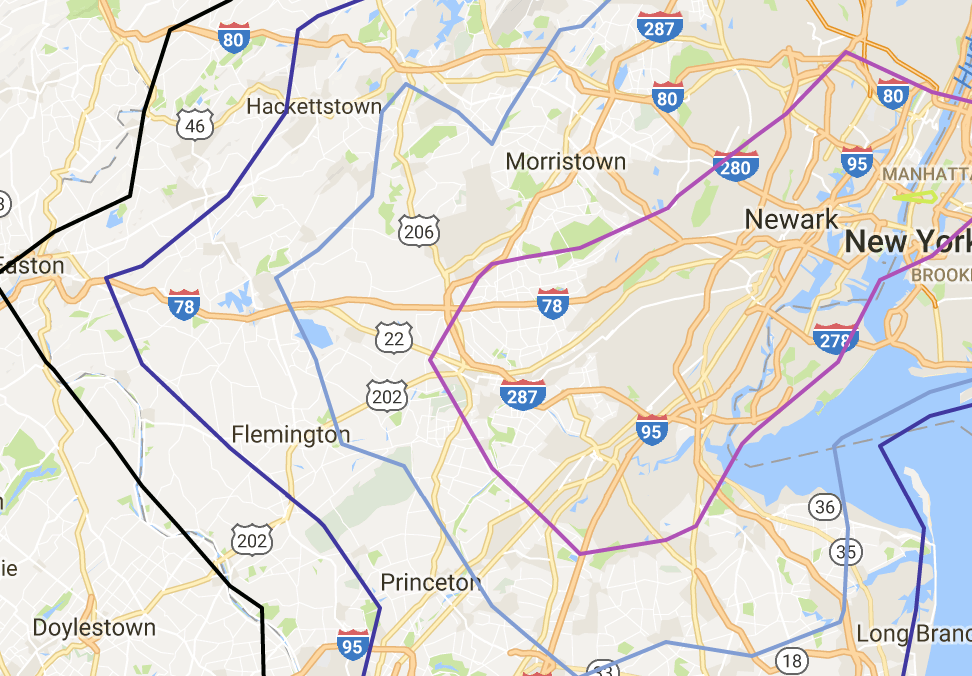

Schools

In Alexandria, we love our house, elementary school, church and community. In order to find the best school system possible, we relied heavily on the rankings assigned by njmonthly.com. Their ranking was a composite of school environment, student performance and student outcomes. These scores were based entirely on data reported by the schools to the state Department of Education (DOE) and published in the School Performance Reports section of the DOE website. You can read more about their methodology at njmonthly.com. We also looked at Great Schools to crosscheck the list. Tim used python, the google geocoding API and google sheets to get geocoordinates for each school. He then was able to pull these into google maps builder and assign a color corresponding to the schools’ rank. While there is a lot more work in the future to better understand the potential at each school, the map below was very helpful for us.

Commute Time

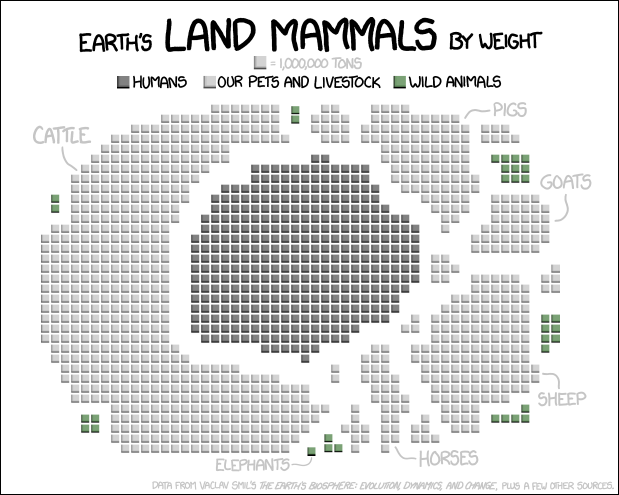

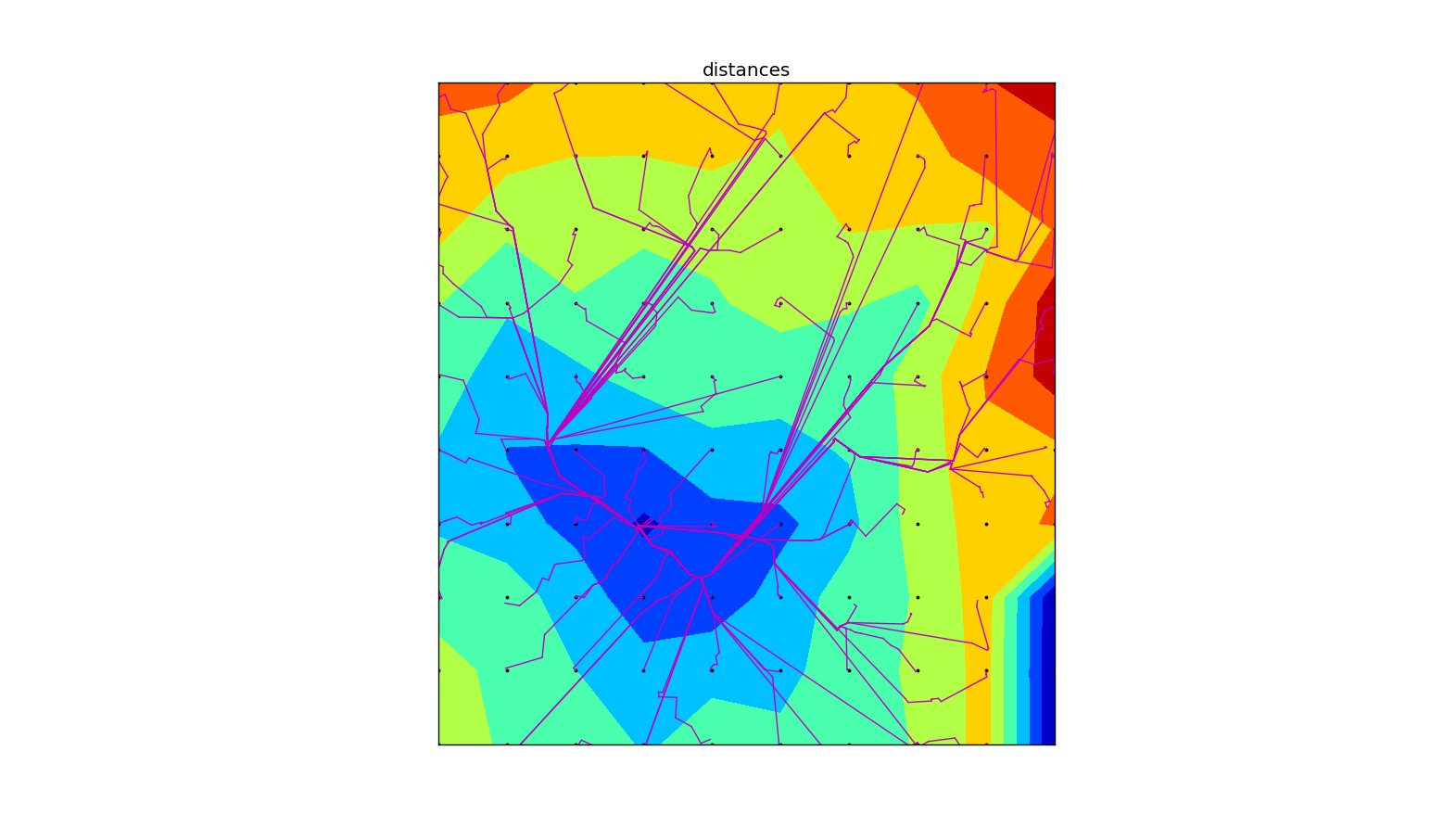

Ok, this is the fun part where Tim’s gets to use his ninja programming skillz. Tim is going to be traveling a lot, but when he is home he will often be in Piscataway, NJ and Manhattan. Nothing online would show the average, maximum or minimum commute times for multiple locations. Additionally, we wanted combined different traffic patterns and the optimal route found by comparing public transit and driving. In order to build this, Tim build a python script that used the google directions api and the associated python library to provide transportation times. He then used matplotlib and basemap to put a grid across the region of interest and then used the contour features to generate contour lines for regions that were 20, 30, 40, 50, 60, and 70 minutes away. This produced lots of plots that helped get a feel of the major transportation routes and how traffic varied by time of day.

Of course, Tim did excursions over time of day and built maps that looked at optimistic- and worst-case scenarios. In the end, it worked best to make each excursion a map layer and to bring in different data sets as we had questions. The most helpful map presented the contour lines made from averaging the best commute from each grid point (in this case a 15 x 15 grid):

How much does commute vary?

The sparkline in each row below shows the commute time for 12 times between 4:30am to 10am each morning. Transit options weren’t possible to Colgate’s technology center, but they generally were to NYC. Commute times below are in minutes. I’m was expecting to see more variance in the commute time. This is either an error in my code or Google really isn’t forecasting commute times based on historical traffic.

| Colgate | NYC | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Driving | Transit | |||||

| Location | mean | Commute | mean | Commute | mean | Commute |

| Westfield, Union | 31 | 46 | 93 | |||

| livingston | 40 | 48 | 118 | |||

| Chatham, Morris | 40 | 45 | 122 | |||

| West Windsor-Plainsboro South, Mercer | 34 | 70 | 132 | |||

| Holmdel, Monmouth | 34 | 59 | ||||

| West Windsor-Plainsboro North, Mercer | 34 | 71 | 195 | |||

| Livingston, Essex | 44 | 43 | 106 | |||

| Montgomery, Somerset | 34 | 78 | ||||

| Haddonfield Memorial, Camden | 64 | 98 | 223 | |||

| Princeton, Mercer | 33 | 71 | 170 | |||

| short hills | 36 | 39 | 137 | |||

| New Providence, Union | 35 | 46 | 138 | |||

| Ridge (Basking Ridge), Somerset | 25 | 53 | 131 | |||

| westfield | 30 | 46 | 85 | |||

| Watchung Hills Regional (Warren), Somerset | 26 | 48 | ||||

| Millburn, Essex | 37 | 40 | ||||

| Glen Rock, Bergen | 55 | 35 | 105 | |||

| Kinnelon, Morris | 52 | 50 | 128 | |||

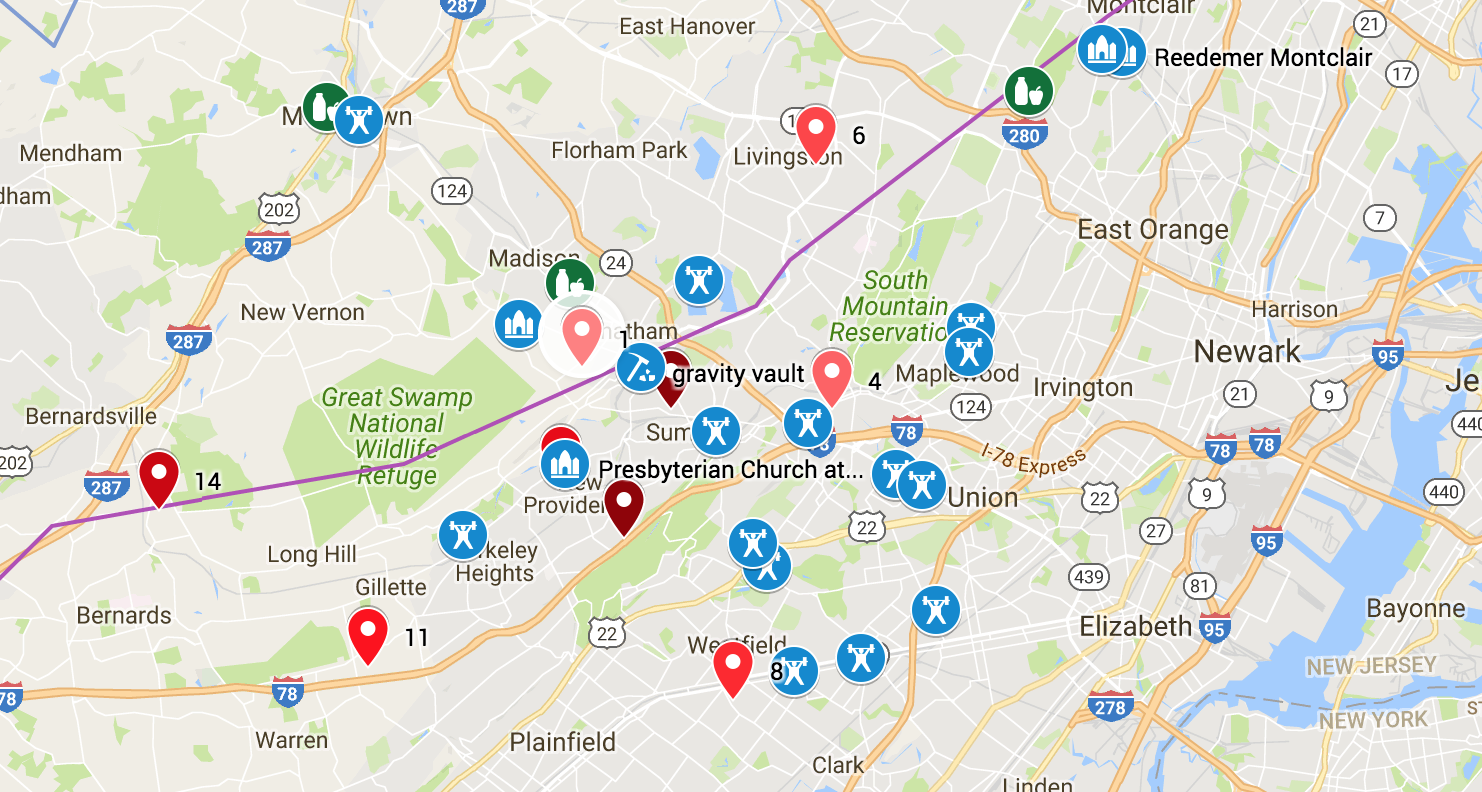

Lifestyle

Our social structure revolves around our church, then around fitness (CrossFit and Rock Climbing Gyms) and other town-centered options (like shopping at Whole Foods, or a charming downtown). We wanted to live as close to the city as possible, while still able to find a nice home with the right school. The most helpful way to incorporate this information was to build several lists and then use the google geocoding API to get the geocoordinates. From here, it was simple to export to CSV and upload into the mashup. This produced this insanely cool composite map.

Results: Potential Locations

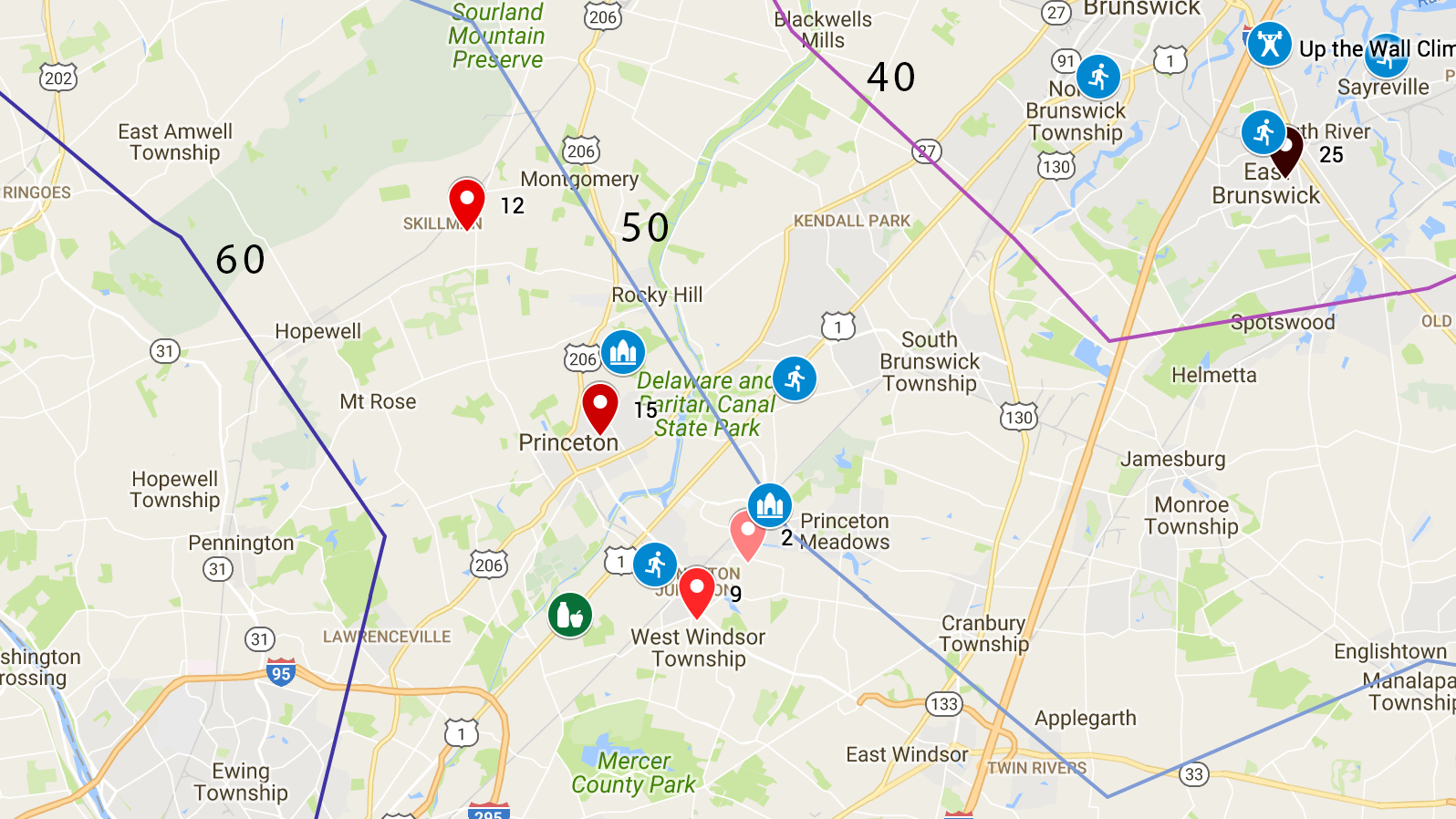

Princeton, Montgomery, West Windsor

We love the downtown, schools and academic atmosphere of Princeton. It is close to cool companies like SRI and major research centers. It also has nice neighborhoods and is very walkable. It has a train to NYC and has good church options. It is much farther from the city than we want to be and the house prices are much higher in Princeton proper when compared with the local area.

Westfield, Milburn, Short Hills, Livingston, Monclair

There was another cluster much closer to the city. We also like the option of attending Redeemer Church of Montclair. However, we hate to give up the university town and high tech feel of the town.

Summary

In all, we now look forward to visiting in person and getting a feel for these neighborhoods. I feel like we have a good map that we can update as we get to know the area better. Hats of to Google for making so much accessible through APIs and for making such nice interfaces to view everything with. Open standards just plain rock.

We put this post together to collect our thoughts, share our code and methodology, but also to help the dialogue with our friends. If you have any thoughts on the above, please email us at tim_and_chrissy@www.theboohers.org.

Resources

Please feel free to use, modify and enjoy the code we wrote for this. Feel free to see and edit our spreadsheet