Reformed Christian Perspective on Israel and Modern Judaism

Some American Christians are rethinking what they believe about Israel and Judaism. Shifting geopolitical realities, rising tensions both domestically and internationally, and increasingly polarized discourse have forced questions that have been long settled for me. But before we can answer “What should Christians think about Jews?”—we need to untangle what we’re actually talking about.

We can call something “Jewish”, when it functions as at least five different categories that we habitually collapse into one:

Ethnicity: Genetic descent from Abraham through Isaac and Jacob

Culture: Rich literary and intellectual traditions, distinctive languages (Yiddish, Ladino, Judeo-Arabic), cuisine and foodways, music (klezmer, liturgical, contemporary), art and cinema, philosophical contributions, scientific achievements, centuries of diaspora experience, humor and storytelling traditions, family and community practices, distinct historical memory and commemoration

Faith: Religious belief and practice ranging from secular to ultra-Orthodox

Geopolitics: The modern State of Israel and Middle Eastern policy

Theology: God’s covenant relationship with His chosen people

And within the category of faith alone, “Judaism” spans an enormous spectrum. Reform Jews may not believe in a personal God. Conservative Jews navigate tradition and modernity. Modern Orthodox professionals may study Talmud daily and some ultra-Orthodox communities reject Zionism and don’t recognize the State of Israel. Many friends are secular Jews who identify culturally but not religiously. Even among the religiously observant, there are vast differences in how they relate to foundational texts—Torah (the five books of Moses), Nevi’im (the Prophets), Ketuvim (the Writings), the Talmud (rabbinic discussions and legal interpretations), Midrash (interpretive commentaries), Kabbalah (mystical traditions), and countless generations of rabbinical responsa. Some communities prioritize halakhic (legal) study, others emphasize ethical teachings, still others focus on mystical experience or philosophical theology.

When we ask “What should the Christian posture be toward Jews?” which Judaism are we discussing? The Hasidic community in Brooklyn? The Reform temple down the street? The Israeli soldier? The Hollywood producer? The Talmud scholar? These aren’t interchangeable categories, and our theology must be precise enough to account for these distinctions—not just in what we believe, but in how we relate, engage, and bear witness.

The confusion isn’t just academic. When we lump together ethnicity, faith, culture, and geopolitics, we end up with theological frameworks that can’t distinguish between critique of Israeli policy, rejection of Talmudic tradition, and hatred of Jewish people. We need to disentangle these threads before we can think biblically about any of them.

In the recent words of Stephen Wise, “Jews get to define Judaism, others get to decide if they accept us as we see ourselves”. That’s fair. My answer then of Who and What is provided by the manifold conversations I’ve had with the people who practice their Jewish faith. For me that means two groups: secular Jews largely in military, tech and/or business and faithful religious Jews I know largely through the classroom or conservative political affiliations.

For the purpose of this post, I’m going to assume we are talking about the theological core and shared beliefs of the Jewish faith today as understood through my personal relationships and a bit of reading.

The Biblical Framework or What Christian Scripture Actually Says

Paul’s treatment of Israel in Romans 11 provides the definitive framework for Reformed thinking about Judaism. He describes a remnant chosen by grace (11:5)—not wholesale abandonment but divine preservation. He speaks of partial hardening, not total rejection (11:25)—Israel’s blindness is temporary and purposeful, not permanent apostasy. Most remarkably, Paul uses present tense—they are “beloved for the sake of their forefathers” (11:28), not were beloved. God’s love for Israel continues in the present, not just the past. The gifts and calling of God are irrevocable (11:29)—God doesn’t break covenants, even when His people stumble.

This language is incompatible with viewing Judaism as a pagan or demonic religion. Paul explicitly warns Gentile believers against arrogance toward the natural branches (11:18-22). If post-Temple Judaism were intrinsically demonic, Paul’s entire argument collapses.

Revelation’s Vision: Israel in God’s Future

Revelation’s vision of the end times offers a striking confirmation of Israel’s enduring place in God’s purposes. When the Apostle John sees the future unfold, he doesn’t witness Israel’s erasure or replacement—he sees their distinct preservation. The 144,000 sealed from the twelve tribes of Israel appear in Revelation 7 and 14, not as a metaphor emptied of ethnic meaning, but as testimony to God’s faithfulness to His covenant people. The New Jerusalem itself bears witness to this continuity and its twelve gates are named for the twelve tribes, inscribed into the architecture of God’s eternal city (Revelation 21:12). Even the apocalyptic measuring of the temple and those who worship there (Revelation 11:1-2) maintains Israel’s specific identity in God’s final purposes. Whether we read these passages literally or symbolically, the theological point remains unshakeable, namely that God has not abandoned His covenant relationship with Israel as a people.

This biblical vision helps us understand what “demonic” actually means in Scripture’s categories. The word isn’t a catch-all for “things Christians disagree with”—it has specific, defined boundaries. Scripture reserves “demonic” language for idol worship and service to false gods (Deuteronomy 32:17; 1 Corinthians 10:20), conscious opposition to Christ as the Antichrist spirit (1 John 2:22), and occult practices and divination explicitly condemned in the Law (Leviticus 19:31; Deuteronomy 18:10-12). These are clear categories with clear markers.

Rabbinic Judaism, even in its tragic rejection of Jesus as Messiah, doesn’t fit these categories. Jews continue to worship the Creator God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob—the same God Christians worship, though they cannot see His full revelation in Christ. They maintain the Hebrew Scriptures as authoritative and binding, the very Scriptures that testify to Jesus. They order their lives around prayer, repentance, and holiness, seeking to live before the God who gave Torah at Sinai. They faithfully preserve the Sabbath, the biblical festivals, and the covenant markers that God Himself instituted. This isn’t apostasy to demons—it’s spiritual blindness to the fulfillment that has come.

The center of gravity remains the God of Israel, not Molech or Baal. This is blindness to fulfillment, not apostasy to paganism.

The Talmud Question: Corruption vs. Apostasy

One argument made recently (by folks in my hometown of Fort Worth) is that a careful reading of the Talmud reveals a wholly corrupted Jewish faith that ancient Jews wouldn’t recognize. But this claim requires significant qualification. First, not all Jews hold the Talmud (the oral tradition) on par with the written tradition. The Jewish world is far more diverse in its relationship to rabbinic texts than many critics acknowledge.

The Talmud does present legitimate concerns for Christians. It can obscure grace under layers of legal reasoning, making the encounter with God’s mercy harder to see. Some passages reflect hostility toward Christianity, shaped by centuries of conflict and persecution. It solidifies a system that, without Christ, cannot ultimately save. Certain mystical traditions drift toward problematic territory that should give us pause. These are real issues that deserve honest theological engagement.

But we must be careful not to mistake corruption for apostasy, or development for departure. The Talmud is fundamentally an in-house Jewish attempt to order life before the God of Israel according to Torah. It’s not a manual for worshiping a different deity. It’s rabbinic Judaism wrestling with the question: How do we remain faithful to the covenant when the Temple is destroyed and the priesthood scattered? This distinction matters enormously when we’re trying to assess whether we’re dealing with blindness to fulfillment or apostasy to demons.

Consider Jesus’ own approach to Pharisaic tradition, which became the foundation for what evolved into rabbinic Judaism. He blasts their additions and burdens in Matthew 23, calling out their hypocrisy and legalistic distortions with searing clarity. Yet in the same breath, He acknowledges “they sit in Moses’ seat,” recognizing their legitimate authority to interpret Torah. He debates within the framework of Jewish tradition, not as an outsider confronting a foreign religion. This is the posture of a reformer calling His people back to covenant faithfulness, not a missionary encountering paganism.

What continues from ancient Judaism to its modern expression tells us something crucial. The same God remains central—the Shema, “Hear, O Israel: the LORD our God, the LORD is one,” is still prayed daily. The same Scriptures are read, studied, and revered. The same covenant markers—circumcision, Sabbath, dietary laws—structure Jewish life. The same fundamental hope persists, even if Messianic expectation is understood differently. Many of the same prayers are still recited, some dating back to Temple times. This isn’t wholesale replacement; it’s recognizable continuity.

What changed after the destruction of the Temple represents adaptation within tradition rather than abandonment of it. Temple sacrifice was replaced by prayer and study, following the prophetic principle that God desires mercy more than sacrifice. Priestly authority gave way to rabbinic interpretation as the community needed new leadership structures. Messianic hope was deferred rather than recognized in Jesus—a tragic blindness, but still hope directed toward the God of Abraham. The oral Torah was codified in Talmud and Midrash to preserve what had been transmitted verbally for generations. Theological emphasis shifted from sacrifice to ethics and law as the community sought ways to maintain covenant relationship without the Temple system.

This is development within the same tradition, not the creation of a new religion. A first-century Pharisee, transported to a modern Orthodox synagogue, would recognize far more than he’d find foreign. He would hear familiar prayers, see familiar rituals, recognize the Torah scroll and its reverent treatment. He might be shocked by some theological developments, puzzled by certain innovations, but he wouldn’t think he’d stumbled into a temple of Baal or Molech. The center of gravity—the God of Israel, the authority of Scripture, the covenant relationship—remains recognizably continuous.

Contemporary Jewish belief spans an enormous spectrum, and any analysis that treats it as monolithic fails before it begins.

Within contemporary Judaism, the diversity of belief and practice is staggering. Ultra-Orthodox communities structure entire lives around intensive Talmud study and strict halakhic observance, often living in insular neighborhoods where religious law governs every detail from sunrise to sunset. Modern Orthodox Jews navigate a different balance, engaging Torah deeply while participating fully in modern professional and cultural life—doctors and lawyers who spend their evenings studying ancient texts. Conservative Judaism attempts to honor historical tradition while applying critical scholarship to its sources, creating communities that look traditional but think historically. Reform Judaism emphasizes ethical monotheism over ritual observance, seeing Judaism primarily as a moral framework rather than a legal system. And millions of secular Jews maintain strong cultural identity—celebrating Passover, mourning the Holocaust, supporting Israel—while holding no particular religious beliefs at all.

The claim that “all rabbinic Jews reject God dwelling with man” reveals a fundamental unfamiliarity with Jewish sources and practice. The concept of the Shekhinah—God’s divine presence dwelling among His people—remains absolutely central to traditional Jewish thought across denominations. Every synagogue service explicitly invokes God’s presence. Hasidic traditions speak constantly of encountering the divine in everyday life. Jewish mysticism, from medieval Kabbalah to modern Hasidism, emphasizes divine immanence with an intensity that would surprise critics. Contemporary Jewish philosophers like Abraham Joshua Heschel and Martin Buber have written profoundly about divine-human encounter. To claim Judaism categorically denies God’s presence is simply false.

When Christians carelessly label Judaism “demonic,” a cascade of consequences follows that extends far beyond theological error. We forget that our own Scriptures emerged from Jewish scribes, that our Savior lived as a Torah-observant Jew, that our first apostles were all Jewish believers who saw Jesus as Messiah, not as founder of a new religion. We undermine Paul’s carefully constructed argument in Romans about Israel’s ongoing significance in God’s purposes. We create space for actual antisemites to claim Christian validation for their hatred. We destroy any credible witness to Jewish communities—who would listen to someone who’s already declared them demonic? And most dangerously, we align ourselves with ideological movements that have historically led to persecution and atrocity.

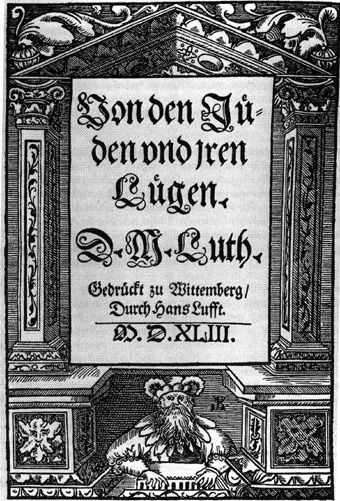

Luther’s Warning: When Evangelical Frustration Becomes Genocidal Blueprint

The Reformed tradition must reckon honestly with how this trajectory has played out in our own history. Martin Luther provides the most sobering example—and for those of us who love Luther, who have been shaped by his theological courage, his biblical insight, his unwavering commitment to justification by faith alone, this reckoning is painful. I count myself among Luther’s admirers. His stand at Worms, his translation of Scripture, his hymns, his exposition of Galatians—these have nourished my faith and the faith of millions. Which makes his writings on the Jews not just historically troubling but personally grievous. We cannot love Luther rightly without lamenting this aspect of his legacy deeply.

In his earlier years, Luther criticized the Catholic Church’s treatment of Jews and held hope for mass Jewish conversion once the Gospel was freed from papal corruption. His 1523 work “That Jesus Christ Was Born a Jew” showed genuine concern for Jewish evangelism and criticized Christian mistreatment.

But when Jews failed to convert in the numbers Luther anticipated, his frustration curdled into something far darker. By 1543, Luther published “On the Jews and Their Lies,” a document so venomous that the Nazis would later display it at Nuremberg rallies. Luther called for burning synagogues, destroying Jewish homes, confiscating prayer books and Talmudic writings, forbidding rabbis from teaching, abolishing safe conduct for Jews on highways, banning usury, and forcing Jews into manual labor. His theological justification? That the Jews’ rejection of Christ proved them to be children of the devil, their synagogues “a den of devils,” their worship demonic.

The progression is instructive and terrifying. Luther began with orthodox Christian conviction—faith in Christ is necessary for salvation. He added urgent evangelistic hope—surely Jews will recognize their Messiah when the Gospel is clearly preached. When reality disappointed—Jews remained unconvinced—theological frustration transmuted into demonization. And demonization inevitably produced calls for persecution. If Jews are demonic, if their worship is satanic, if their very presence pollutes Christian society, then violence becomes not just permissible but pious.

Four centuries later, Nazi propagandists didn’t have to invent Christian antisemitism—they simply dusted off Luther and gave his recommendations modern implementation. When Kristallnacht came on this day (9 Nov) in 1938, synagogues burned across Germany on November 9th—Martin Luther’s birthday. The switch can happen: righteous evangelical urgency can become dark ethnic hatred; theological conviction can become demonization.

The lesson isn’t that we should soft-pedal the Gospel or pretend Jewish rejection of Christ doesn’t matter. Luther was right that Jesus is the only way to salvation. He was right that post-Temple Judaism cannot save. He was catastrophically, damnably wrong in moving from “Jews need Christ” to “Jews are demonic” to “Jews should be persecuted.” The slide from the first to the second happens when we lose Paul’s nuance in Romans 11. The slide from the second to the third is inevitable—it’s simply a matter of time and political opportunity.

A faithful Reformed perspective maintains what might seem like contradictory truths, holding them in tension as Scripture does. Salvation is in Christ alone—any religious system that rejects Jesus cannot ultimately save. Judaism without Christ remains incomplete and broken, with the veil over Moses still unlifted, as Paul describes in 2 Corinthians. Yet simultaneously, Israel remains beloved for the sake of the patriarchs, their gifts and calling irrevocable. The root of the olive tree is holy, and we Gentile believers are grafted into Israel’s story, not the reverse. And crucially for our historical moment, antisemitism—the hatred of Jewish people—stands in direct opposition to God’s purposes and the Gospel itself. These truths don’t contradict; they complete each other.

This framework allows us to evangelize Jewish people with urgency and love, understanding that faith in Christ is essential for salvation while recognizing we’re speaking to those who already know the God of Abraham. It enables us to oppose antisemitism wherever it emerges—whether in progressive spaces that cloak hatred in anti-Zionism or in conservative circles that traffic in conspiracy theories. We can appreciate Judaism’s remarkable preservation of Scripture and its ongoing witness to monotheism, even while maintaining that this witness remains incomplete without Christ. Most importantly, we can hold theological clarity without resorting to demonization, recognizing the profound mystery of Israel’s future restoration that Paul describes in Romans 11:25-26.

These theological commitments have concrete implications for how Christians engage the world today. In theological discussion, we must reject the simplistic “Judaism is demonic” rhetoric that has gained traction in some corners of the internet and most alarmingly in the Church. The distinction between spiritual blindness and pagan apostasy isn’t semantic hairsplitting—it’s the difference between biblical fidelity and dangerous error. Before making sweeping pronouncements about Judaism, Christians should immerse themselves in Romans 9-11, where Paul wrestles with these very questions with far more nuance than most contemporary commentators manage.

In political engagement, the stakes are even higher. Christians must refuse to platform antisemites, regardless of how much we might agree with their positions on other issues. Supporting Israel’s right to exist doesn’t require blind endorsement of every policy decision, just as loving Jewish neighbors doesn’t mean abandoning theological convictions. But we must be clear—theological disagreement never justifies persecution, marginalization, or hatred. When antisemitism appears in progressive spaces or conservative ones, Christians must call it out with equal vigor.

The most transformative engagement, though, happens in personal relationships. Building genuine friendships with Jewish neighbors, learning about Judaism from practicing Jews rather than plucking random passages from the Talmud to construct caricatures, sharing the Gospel with love rather than contempt—these ordinary interactions matter more than grand theological pronouncements. Christians can celebrate what Judaism has faithfully preserved through centuries of persecution while pointing to its fulfillment in Christ. We can study together, disagree deeply, and still recognize our shared heritage in the God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob.

Church teaching bears special responsibility in this moment. Pastors must preach the whole counsel of Scripture on Israel, including the difficult passages that don’t fit neatly into either supersessionist or dispensationalist categories. Replacement theology that erases Israel’s ongoing significance contradicts Paul’s explicit teaching, but so does any framework that ignores Judaism’s tragic blindness to its own Messiah. Churches must teach Christian history honestly, including the shameful legacy of Christian antisemitism that provided theological cover for persecution and genocide. Only by facing this history squarely can we prepare our congregations to engage Jewish friends, neighbors, and colleagues with both theological clarity and genuine love.

To declare Judaism “demonic” is to saw off the branch we’re sitting on. Christianity emerges from Judaism, fulfills Judaism’s hopes, and shares Judaism’s Scriptures. Our Savior was a Torah-observant Jew who prayed the Shema, kept the Sabbath, and celebrated Passover. The apostles were Jews who saw Jesus as Israel’s Messiah, not a foreign deity. Yes, modern Judaism’s rejection of Jesus is spiritually fatal. Yes, the Talmudic tradition includes problematic elements. Yes, we must evangelize Jewish people with urgency. But we must do so recognizing what Paul knew—this is family business. We’re dealing with elder brothers who can’t see the family resemblance in the One they reject, not strangers worshiping foreign gods. They are “enemies for your sake” but “beloved for the sake of the fathers” (Romans 11:28).

The Reformed tradition at its best provides the clarity our moment demands. Unwavering commitment to salvation in Christ alone, coupled with deep respect for God’s irrevocable calling of Israel. This isn’t theological compromise—it’s biblical fidelity. The way forward isn’t through demonization but through faithful witness, proclaiming Christ as the fulfillment of Israel’s hope while standing firmly against those who would harm the people through whom salvation came to the world. This is the Reformed position, the biblical position, and the only position that takes seriously both the Gospel’s exclusivity and God’s covenant faithfulness. As Paul concludes his meditation on Israel’s mystery—”Oh, the depth of the riches both of the wisdom and knowledge of God! How unsearchable are His judgments and His ways past finding out!” (Romans 11:33). That humility—not internet boldness or reactionary provocations—should mark our engagement with the mystery of Israel and the Jewish people.

Be the first to write a comment.