To Act or To Trust: A false Choice?

There’s a pastor in Moscow, Idaho who wants you to fight. Doug Wilson and the Christian Nationalists tell us the culture is at stake—we must engage, strategize, win. Anything less is retreat, surrender, unfaithfulness. This resonates with me. I’m a military man, trained and willing to fight. I’m also a conservative, convicted to preserve the good in society. This requires action and courage. My friends who attend his church are wise, committed and productive citizens.

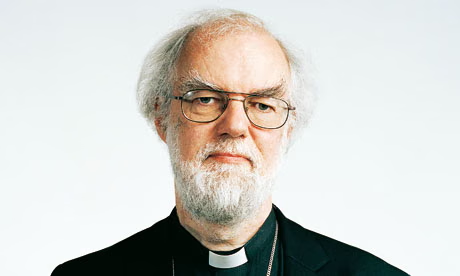

However, a recent visit with a friend re-introduced me to Rowan Williams, who offers not “theology that bites back” but the mystic’s voice: “Consider the lilies. They neither toil nor spin.” Trust God. Let go. This sounds like wisdom—until it sounds like fatalism. Or worse, Islam’s inshallah: whatever will be, will be.

Which is it? Fight for culture or let God do the fighting?

The question feels urgent, binary. Kierkegaard would recognize it immediately—the tyranny of “Either/Or” thinking. Pick a side. You’re either with us or against us.

Rowan Williams—Welsh poet, patristics scholar, former Archbishop of Canterbury—spent a decade frustrating everyone by refusing to choose.

During his 2002-2012 tenure, activists wanted decisive stands. Conservatives wanted tradition defended. Progressives wanted him leading the charge. Everyone wanted a general willing to marshal troops.

Instead, they got a contemplative who wrote poetry, translated fourth-century mystics, and gave maddeningly nuanced answers. When pressed on sexuality debates threatening to split global Anglicanism, he chose patient dialogue over ideological purity. The right called him weak. The left called him complicit.

But Williams wasn’t confused. He was inhabiting the tension rather than resolving it. He learned this from Christianity’s most unlikely revolutionaries—the Desert Fathers.

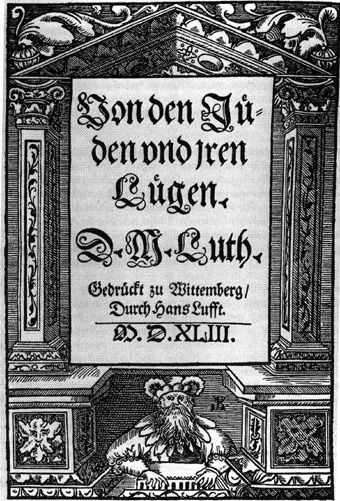

In his book Silence and Honey Cakes, Williams introduces these strange rebels. When fourth-century Christianity became the empire’s official religion and bishops wore imperial robes, thousands of Christians fled to the Egyptian desert.

These weren’t quietists. They saw that “winning” the culture war meant losing everything that mattered. The empire embraced the church; the church became imperial. To bishops negotiating with emperors, accumulating wealth, defining orthodoxy through political power, the Desert Fathers said: No.

They didn’t storm halls of power or write manifestos. They walked into the wilderness with nothing and sat down.

And from that wilderness, they changed everything.

Here’s what Williams sees: their withdrawal was the most political act imaginable. They weren’t escaping the culture war—they were fighting it on completely different terms.

The empire said power comes from influence, wealth, control. The Desert Fathers built nothing, owned nothing, controlled nothing.

The culture said identity comes from role, status, accomplishments. The Desert Fathers literally forgot their names in silence.

The economy said value equals productivity. The Desert Fathers sat absolutely still for hours, producing nothing, calling it the world’s most important work.

This drove visitors crazy. Pilgrims traveled weeks seeking wisdom, and the hermit would say: “Go, sit in your cell, and your cell will teach you everything.”

It sounds like non-engagement. But Williams argues the opposite: the desert wasn’t retreat from reality—it was the only place to see reality clearly.

The activist impulse runs deep in American Christianity. Save the culture. Win the argument. Build the institution. Doug Wilson’s approach resonates because it feels faithful, muscular. “Faith without works is dead,” right?

But Williams asks: What if all your frantic activity is baptized anxiety? What if your need to “fight for the culture” is actually ego—your need to matter, to win? What if activism is driven not by love but fear—fear of irrelevance, of God not showing up unless you make it happen?

The Desert Fathers called this logismoi—the swirling thoughts driving us, compulsions masquerading as virtues. Until you sit still enough to see these illusions clearly, every “good work” is contaminated by them.

In the desert, they learned apatheia—not apathy, but freedom from reactive passions. Acting from clarity rather than compulsion, love rather than fear, trust rather than control.

This drove Williams’ critics mad. They wanted reaction. He offered contemplation. They wanted tribal certainty. He offered nuanced discernment. They wanted a general. He gave them a monk.

But doesn’t this collapse into Islamic fatalism? If we’re supposed to trust God, why act at all?

Here’s Williams’ crucial synthesis:

The fatalist says: “My actions don’t matter, so why try?” Despair disguised as piety.

The activist says: “Everything depends on me, so I must never rest.” Pride disguised as faithfulness.

The contemplative says: “God is acting, and I get to participate—but the outcome isn’t mine to control.” This is freedom.

Look at Jesus. Forty days in the desert before public ministry. Regular withdrawal sustaining public work. He engaged culture—healing, teaching, confronting power. But he acted from deep rootedness in the Father, from abundance not anxiety.

The night before his arrest, Peter draws a sword. Jesus says: put it away. Not because he’s passive, but because he’s operating from completely different understanding of power. That’s not fatalism. That’s the most radical trust in human history.

Kierkegaard’s Either/Or presents seemingly incompatible life choices: aesthetic or ethical, pleasure or duty. But Kierkegaard knew the title itself is the trap. The mature person doesn’t choose between them; they integrate them at a higher level in the “religious” stage.

Williams does the same with contemplation and action. We must trust and act. Withdraw and engage. Cultivate silence and speak prophetically.

Think of it like breathing. Inhale: contemplation, withdrawal, receiving. Exhale: action, engagement, giving. You can’t live by only inhaling—you’ll burst. You can’t live by only exhaling—you’ll collapse.

The question isn’t calculating the perfect ratio. It’s: Are you rooted deeply enough to engage wisely?

But here’s where Williams’ approach faces its most devastating critique: What about when evil demands immediate action?

Consider the lilies while babies are being aborted? Cultivate silence while DEI policies systematically discriminate? Would Williams have been Churchill or Chamberlain?

Edmund Burke haunts us: “The only thing necessary for the triumph of evil is for good men to do nothing.” Hitler didn’t need more Rowan Williams types—he needed the church to fight.

When Bonhoeffer returned to Germany in 1939, he chose conspiracy and resistance over safe contemplation. When Wilberforce fought the slave trade for decades, he wasn’t told to “consider the lilies.”

So is Williams wrong?

No—but he’s incomplete if we don’t understand what contemplation actually produces.

The Desert Fathers weren’t pacifists—they were the fiercest warriors against evil. But they understood the deepest evils are spiritual, and you can’t fight spiritual battles with carnal weapons. Athanasius, who fought Arianism for decades, learned his theology from Anthony of the desert. The contemplative produced the fighter.

Those silent monks became the theological backbone resisting imperial heresy. When emperors demanded doctrinal compromise, the desert tradition held firm. Their withdrawal gave them clarity and courage to resist.

Contemplation isn’t an alternative to fighting evil—it’s what equips you to fight the right battles in the right way for the right reasons.

The activist who never contemplates will fight—but against what? With what weapons? Driven by what spirit? We’ve seen conservatives become indistinguishable from the left in tactics, spirit, tribalism. They’re fighting like the world fights, which means they’ve already lost.

DEI is evil when it judges people by immutable characteristics rather than character and competence. Fight it. But how? By becoming equally tribal, equally discriminatory—just reversed? That’s not winning; that’s becoming what you oppose.

The pro-life movement’s greatest victories haven’t come from politicians screaming on cable news—they’ve come from crisis pregnancy centers, changed hearts, decades of patient work.

So practically, what does this mean?

First, check your motivations. Is this flowing from prayer or anxiety? From love or ego? Anxious activism burns out or becomes monstrous.

Second, cultivate depth. If your activism isn’t rooted in regular silence, solitude, prayer—it will corrupt you. Bonhoeffer practiced the disciplines even while plotting against Hitler.

Third, embrace the long game. The Desert Fathers planted seeds that wouldn’t flower for generations. Wilberforce fought twenty years before victory.

Fourth, go smaller, deeper, truer. Don’t grasp for cultural dominance. Build communities of alternative practice. The early church didn’t defeat Rome by winning elections—they built a parallel society so compelling the empire converted.

Fifth, know your real enemies. The Desert Fathers’ battles were internal—pride, vainglory, anger. The same spiritual evil producing DEI—pride disguised as compassion—lives in your heart too.

After a decade trying to hold together a fracturing communion, Williams stepped down and returned to teaching, writing, poetry. Some saw defeat. But maybe it was the most desert move of all: releasing the need to control outcomes, trusting God with the church.

Since leaving Canterbury, Williams has written more explicitly about economic justice, climate change, empire. Freed from institutional power, he’s become more pointed. The withdrawal enabled deeper engagement.

The question Williams forces us to face isn’t whether to engage or trust, fight or pray. It’s: From what source are you living?

Are you acting from union with God, or from anxious need to make something happen? Is your engagement an overflow of contemplation, or a substitute for it?

The Desert Fathers fled not because they didn’t care about the world, but because they loved it too much to let empire define what caring looks like.

Williams spent a decade demonstrating you can be deeply engaged while refusing to let the world’s anxiety determine your response. You can lead without grasping. Care without controlling. Act decisively while holding outcomes loosely.

The culture won’t be saved by Christians who trust God so much they do nothing. Nor by Christians who fight so hard they become indistinguishable from every other power-seeking tribe.

It might be saved by communities who’ve been to the desert. Who’ve sat still enough to see their illusions clearly. Who act not from anxiety but abundance. Who fight not from fear but love. Who engage not to win but to witness.

Who trust God enough to act. And act in ways that demonstrate trust.

The Desert Fathers didn’t defeat empire by organizing coalitions. They defeated it by refusing to let it define reality. By living so differently that people traveled hundreds of miles to ask: “How do you have such peace?”

And when pilgrims arrived expecting great wisdom, the hermits would say: “Go sit in your cell, and your cell will teach you everything.”

Maybe that’s exactly what we need to hear.

Not because culture doesn’t need engagement, but because we can’t engage faithfully until we’ve learned to sit still. Until we’ve discovered that God’s kingdom comes not by might nor power, but by a Spirit we can only encounter in silence.

Then—only then—when we speak, we’ll have something worth saying. When we act, we’ll act from depth. When we fight, we’ll fight for the right things in the right ways.

We’ll fight like people who’ve learned to trust. And trust like people free to act.

Which is to say: we’ll breathe. In and out. Contemplation and action. Desert and city.

Both. And. Not either. Or.

Maybe the way forward isn’t choosing between the culture warrior and the contemplative. It’s becoming the kind of person who’s been silent enough to have something worth saying when they speak.