Autonomy

I lead autonomy at Boeing. What exactly do I do?

We engineers have kidnapped a word that doesn’t belong to us. Autonomy is not a tech word, it’s the ability to act independently. It’s freedom that we design in and give to machines.

It’s also a bit more. Autonomy is the ability to make decisions and act independently based on goals, knowledge, and understanding of the environment. It’s an exploding technical area with new discoveries daily and maybe one of the most exciting tech explosions in human history.

We can fall into a trap that autonomy is code — a set of instructions governing a system. Code is just language, a set of signals, it’s not a capability. We remember Descartes for his radical skepticism or for giving us the X and Y axes, but he is the first person who really get credit for the concept of autonomy with his “thinking self” or the “cogito.” Descartes argued that the ability to think and reason independently was the foundation of autonomy.

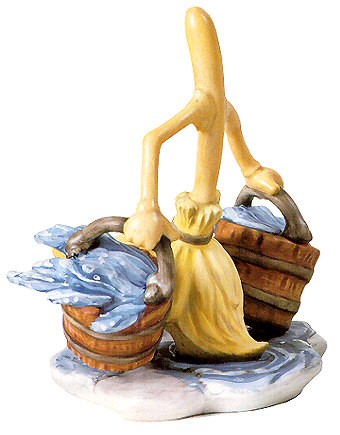

But I work on giving life and freedom to machines, what does that look like? Goethe gives us a good mental picture in his Der Zauberlehrling (later adapted in Disney’s “Fantasia”) when the sorcerer’s apprentice attempts to use magic to bring a broom to life to do his chores only to lose his own autonomy as chaos ensues.

Giving our human-like freedom to machines is dangerous and every autonomy story gets at this emergent danger. This is why autonomy and ethics are inextricably linked and “containment” (keeping AI from taking over) or “alignment” (making AI share our values) are the most important (and challenging) technical problems today.

A lessor known story gets at the promise, power and peril of autonomy. The Golem of Prague emerged from Jewish folklore in the 16th century. From centuries of pogroms, the persecuted Jews of Eastern Europe found comfort in the story of a powerful creature with supernatural strength who patrolled the streets of the Jewish ghetto in Prague, protecting the community from attacks and harassment.

The golem was created by a rabbi named Mahara using clay from the banks of the Vltava River. He brought the golem to life by placing a shem (a paper with a divine name) into its mouth or by inscribing the word “emet” (truth) on its forehead. One famous story involves the golem preventing a mob from attacking the Jewish ghetto after a priest had accused the Jews of murdering a Christian child to use their blood for Passover rituals. The golem found the real culprit and brought them to justice, exonerating the Jewish community.

However, as the legend goes, the golem grew increasingly unstable and difficult to control. Fearing that the golem might cause unintended harm, the Maharal was forced to deactivate it by removing the shem from its mouth or erasing the first letter of “emet” (which changes the word to “met,” meaning death) from its forehead. The deactivated golem was then stored in the attic of the Old New Synagogue in Prague, where some say it remains to this day.

Power, protection of the weak, emergent properties, containment. The whole autonomy ecosystem in one story. From Terminator to Her, why does every autonomy story go bad in some way? It’s fundamentally because giving human agency to machines is playing God. My favorite modern philosopher, Alvin Plantinga describes the qualifications we can accept as a creator: “a being that is all-powerful, all-knowing, and wholly good.” We share none of those properties, do we really have any business playing with stuff this powerful?

The Technology of Autonomy

We don’t have a choice, the world is going here and there is much good work to be done. Engineers today have the honor to be modern days Maharal’s — building safer and more efficient systems with the next generation of autonomy. But what specifically are we building and how do we build it so it’s well understood, safe and contained?

A good autonomous system requires software (intelligence), a system of trust and human interface/control. At its core, autonomy is systems engineering. It is the ability to take dynamic and advanced technologies and make them control a system in effective and predictable ways. The heart of this capability is software. To delegate control to a system it needs software to control perception, decision-making capability, action and communication. Let’s break these down.

- Perception: An autonomous system must be able to perceive and interpret its environment accurately. This involves sensors, computer vision, and other techniques to gather and process data about the surrounding world.

- Decision-making: Autonomy requires the ability to make decisions based on the information gathered through perception. This involves algorithms for planning, reasoning, and optimization, as well as machine learning techniques to adapt to new situations.

- Action: An autonomous system must be capable of executing actions based on its decisions. This involves actuators, controllers, and other mechanisms to interact with the physical world.

- Communication: Autonomous systems need to communicate and coordinate with other entities, whether they be humans or other autonomous systems. This requires protocols and interfaces for exchanging information and coordinating actions.

Building autonomous systems requires a diverse set of skills, including ethics, robotics, artificial intelligence, distributed systems, formal analysis, and human-robot interaction. Autonomy experts have a strong background in robotics, combining perception, decision-making, and action in physical systems, and understanding the principles of kinematics, dynamics, and control theory. They are proficient in AI techniques such as machine learning, computer vision, and natural language processing, which are essential for creating autonomous systems that can perceive, reason, and adapt to their environment. As autonomous systems become more complex and interconnected, expertise in distributed systems becomes increasingly important for designing and implementing systems that can coordinate and collaborate with each other. Additionally, autonomy experts understand the principles of human-robot interaction and can design interfaces and protocols that facilitate seamless communication between humans and machines.

As technology advances, the field of autonomy is evolving rapidly. One of the most exciting developments is the emergence of collaborative systems of systems – large groups of autonomous agents that can work together to achieve common goals. These swarms can be composed of robots, drones, or even software agents, and they have the potential to revolutionize fields such as transportation, manufacturing, and environmental monitoring.

How would a boxer box if they could instantly decompose into a million pieces and re-emerge as any shape? Differently.

What is driving all this?

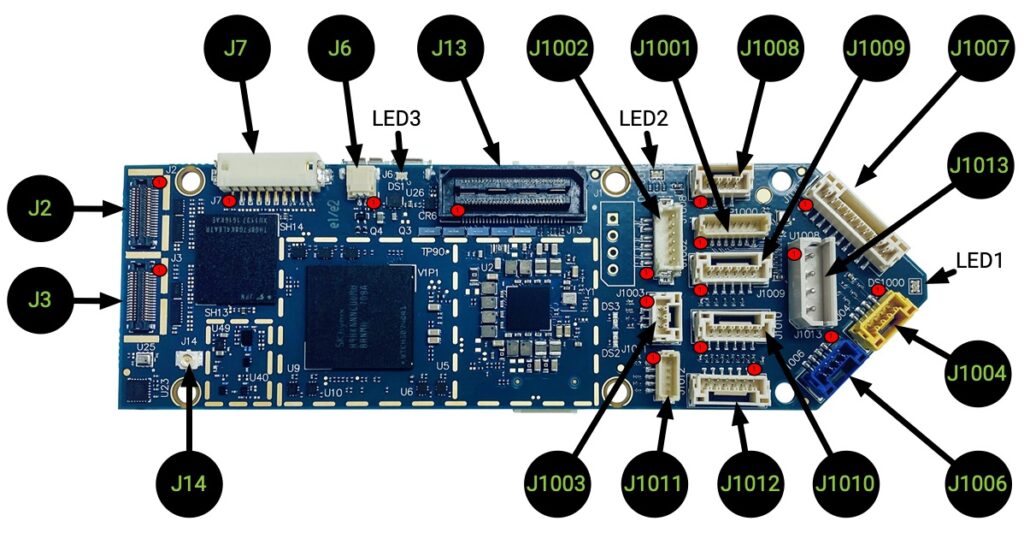

Two significant trends are rapidly transforming the landscape of autonomy: the standardization of components and significant advancements in artificial intelligence (AI). Components like VOXL and Pixhawk are pioneering this shift by providing open-source platforms that significantly reduce the time and complexity involved in building and testing autonomous systems. VOXL, for example, is a powerful, SWAP-optimized computing platform that brings together machine vision, deep learning processing, and connectivity options like 5G and LTE, tailored for drone and robotic applications. Similarly, Pixhawk stands as a cornerstone in the drone industry, serving as a universal hardware autopilot standard that integrates seamlessly with various open-source software, fostering innovation and accessibility across the drone ecosystem. All this means you don’t have to be Boeing to start building autonomous systems.

These hardware advancements are complemented by cheap sensors, AI-specific chips, and other innovations, making sophisticated technologies broadly affordable and accessible. The common standards established by these components have not only simplified development processes but also ensured compatibility and interoperability across different systems. All the ingredients for a Cambrian explosion in autonomy.

The latest from NVIDIA and Google

These companies are building a bridge from software to real systems.

The latest advancements from NVIDIA’s GTC and Google’s work in robotics libraries highlight a pivotal moment where the realms of code and physical systems, particularly in digital manufacturing technologies, are increasingly converging. NVIDIA’s latest conference signals a transformative moment in the field of AI with some awesome new technologies:

- Blackwell GPUs: NVIDIA introduced the Blackwell platform, which boasts a new level of computing efficiency and performance for AI, enabling real-time generative AI with trillion-parameter models. This advancement promises substantial cost and energy savings.

- NVIDIA Inference Microservices (NIMs): NVIDIA is making strides in AI deployment with NIMs, a cloud-native suite designed for fast, efficient, and scalable development and deployment of AI applications.

- Project GR00T: With humanoid robotics taking center stage, Project GR00T underlines NVIDIA’s investment in robotics learning and adaptability. These advancements imply that robots will be integral to motion and tasks in the future.

The overarching theme from NVIDIA’s GTC was a strong commitment to AI and robotics, driving not just computing but a broad array of applications in industry and everyday life. These developments hold potential for vastly improved efficiencies and capabilities in autonomy, heralding a new era where AI and robotics could become as commonplace and influential as computers are today.

Google is doing super empowering stuff too. Google DeepMind, in collaboration with partners from 33 academic labs, has made a groundbreaking advancement in the field of robotics with the introduction of the Open X-Embodiment dataset and the RT-X model. This initiative aims to transform robots from being specialists in specific tasks to generalists capable of learning and performing across a variety of tasks, robots, and environments. By pooling data from 22 different robot types, the Open X-Embodiment dataset has emerged as the most comprehensive robotics dataset of its kind, showcasing more than 500 skills across 150,000 tasks in over 1 million episodes.

The RT-X model, specifically RT-1-X and RT-2-X, demonstrates significant improvements in performance by utilizing this diverse, cross-embodiment data. These models not only outperform those trained on individual embodiments but also showcase enhanced generalization abilities and new capabilities. For example, RT-1-X showed a 50% success rate improvement across five different robots in various research labs compared to models developed for each robot independently. Furthermore, RT-2-X has demonstrated emergent skills, performing tasks involving objects and skills not present in its original dataset but found in datasets for other robots. This suggests that co-training with data from other robots equips RT-2-X with additional skills, enabling it to perform novel tasks and understand spatial relationships between objects more effectively.

These developments signify a major step forward in robotics research, highlighting the potential for more versatile and capable robots. By making the Open X-Embodiment dataset and the RT-1-X model checkpoint available to the broader research community, Google DeepMind and its partners are fostering open and responsible advancements in the field. This collaborative effort underscores the importance of pooling resources and knowledge to accelerate the progress of robotics research, paving the way for robots that can learn from each other and, ultimately, benefit society as a whole.

More components, readily available to more people will create a cycle with more cyber-physical systems with increasingly sophisticated and human-like capabilities.

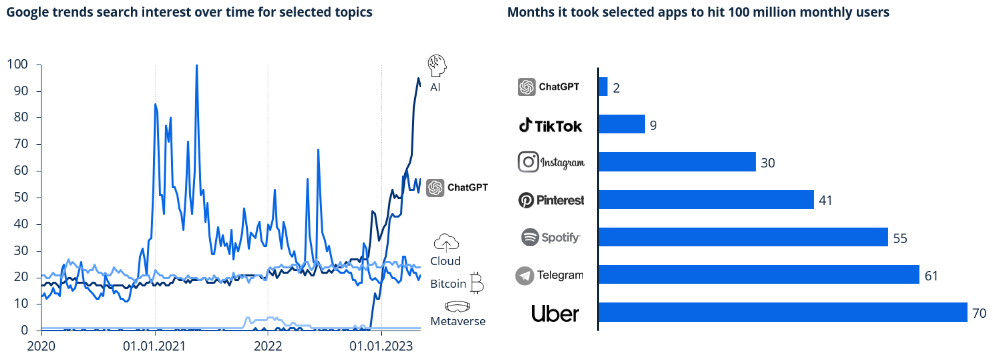

Parallel to these hardware advancements, AI is experiencing an unprecedented boom. Investments in AI are yielding substantial results, driving forward capabilities in machine learning, computer vision, and autonomous decision-making at an extraordinary pace. This synergy between accessible, standardized components and the explosive growth in AI capabilities is setting the stage for a new era of autonomy, where sophisticated autonomous systems can be developed more rapidly and cost-effectively than ever before.

Autonomy and Combat

What does all of this mean for modern warfare? Everyone has access to this tech and innovation is rapidly bringing these technologies into combat. We are right in the middle of a new powerful technology that will shape the future of war. Buckle up.

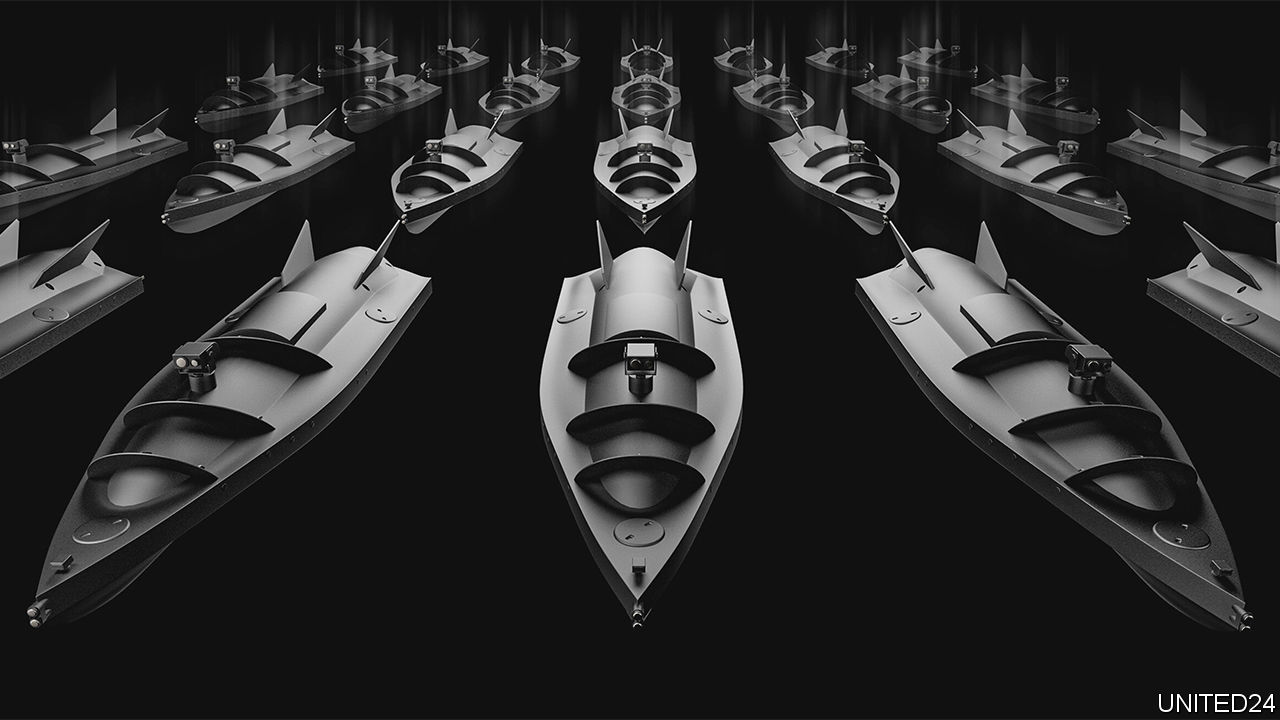

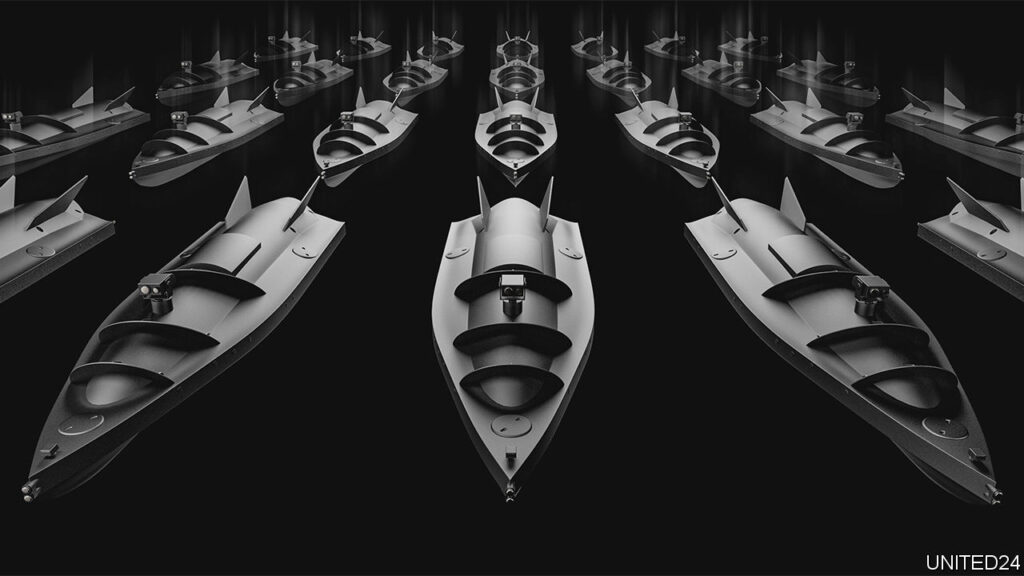

Let’s look at this in the context of Ukraine. The Ukraine-Russia war has seen unprecedented use of increasingly autonomous drones for surveillance, target acquisition, and direct attacks, altering traditional warfare dynamics significantly. The readily available components combined with rapid iteration cycles have democratized aerial warfare, allowing Ukraine to conduct operations that were previously the domain of nations with more substantial air forces and level the playing field against a more conventionally powerful adversary. These technologies are both accessible and affordable. While drones contribute to risk-taking by allowing for expendability, they don’t necessarily have to be survivable if they are numerous and inexpensive.

The conflict has also underscored the importance of counter-drone technologies and tactics. Both sides have had to adapt to the evolving drone threat by developing means to detect, jam, or otherwise neutralize opposing drones. Moreover, drones have expanded the information environment, allowing unprecedented levels of surveillance and data collection which have galvanized global support for the conflict and provided options to create propaganda, to boost morale, and to document potential war crimes.

The effects are real. More than 200 companies manufacture drones within Ukraine and some estimates show that 30% of the Russian Black Sea fleet has been destroyed by uncrewed systems. Larger military drones like the Bayraktar TB2 and Russian Orion have seen decreased use as they became easier targets for anti-air systems. Ukrainian forces have adapted with smaller drones, which have proved effective at a tactical level, providing real-time intelligence and precision strike capabilities. Ukraine has the capacity to produce 150,000 drones every month, and may be able to produce two million drones by the end of the year and they have struck over 20,000 Russian targets.

As the war continues, innovations in drone technology persist, reflecting the growing importance of drones in modern warfare. The conflict has shown that while drones alone won’t decide the outcome of the war, they will undeniably influence future conflicts and continue to shape military doctrine and strategy.

Autonomy is an exciting and impactful field and the story is just getting started. Stay tuned.