Tale of Two Cities: Faith and Progress

Around 1710, the English theologian Thomas Woolston wrote that Christianity would be extinct by the year 1900. In 1822, Thomas Jefferson predicted there is not a young man now living in the United States who will not die a Unitarian. While these predictions didn’t pan out, we live in a world that neither of them would recognize. Much would surprise them and some would downright shock them.

Recently, my family had the opportunity for two amazing meals: one in NYC’s SoHo district and the other in the old town of Geneva. [^1] Both dinners were served against a backdrop of two gay pride events. In NYC, I parked my car under a large cartoon drawing of two men engaged in a graphic sex act. This was surrounded by other lewd, pornographic, pictures. I tried to usher my kids quickly underneath several of them. While dining, I had explain to my 10 year old boy why a man in front of the restaurant was wearing a leather mask and being pulled around on a collar. When we went to a french bakery in the village, we were confronted with even more garish sights. It seems homosexual civil rights are also accompanied by the introduction of pornography into the public square. I know my friends in San Francisco, have daily experiences like this.

As a business person, it was odd to watch the SoHo neighborhood, the pinnacle of American consumerism, transform into an intense contest to turn a cultural phenomenon into a commercial opportunity. It wasn’t enough to fly a flag outside their stores. In an intense effort to cash in on the latest trend, they filled their window displays with custom designed rainbow colored merchandise. To ignore the event, would give them a fate no struggling retailer can afford: cultural irrelevance. Today, as I walked down fifth avenue the flags are gone and the window displays are changed, almost as an acknowledgement that their core identity, of say a shoe store, is not a sexual orientation.

The next dinner out was early July in Geneva. Here the Jet d’Eau was changed into rainbow colors and every crosswalk was adorned with the rainbow flag. While the commercial world there didn’t seem to care (Breguet and Patek were Swiss neutral), the city was clearly all in: Swiss flags were equally matched by rainbow flags as if they were the backdrop of a diplomatic summit between nationalism and sexual freedom. It was interesting how non-commercial it was, probably since the Louis Vutton store was selling to middle eastern and asian countries less obsessed with putting sex in every product. In fact, the commercial abstention was mutual. There were ubiquitous graffiti and post-bills declaring we’re here, we’re queer and we are not going shopping. When I took my kids to reformation park, there were men in speedos climbing the statue of John Calvin and swimming in the water in front of him. They hung profane signs on the reformer and his three colleagues while the police watched and the band blasted techno music. While some friends will see this as an exciting example of societal progress, I’m pretty sure Calvin himself would disagree. I was denied the opportunity to show the heroes of the reformation, and confronted with explaining the scene before us.

What we can all agree on, is that society is rapidly changing. I know enough about history to know that societal change and the collapse of former norms are expected, but these two meals forced me to think about the broader arc of all this. Hegel convinced me that history is neither neutral, cyclical nor static: it is going somewhere. Each of us has a responsibility to estimate where that is and to do our best to positively influence all of this.

So where are we going and why? These times seem uncertain, but I know:

- the election of Donald Trump (and other populist statists) is a symptom of public fear and not a cause

- we are accumulating debt at high levels

- technology is displacing jobs, causing distrust, and changing our brains

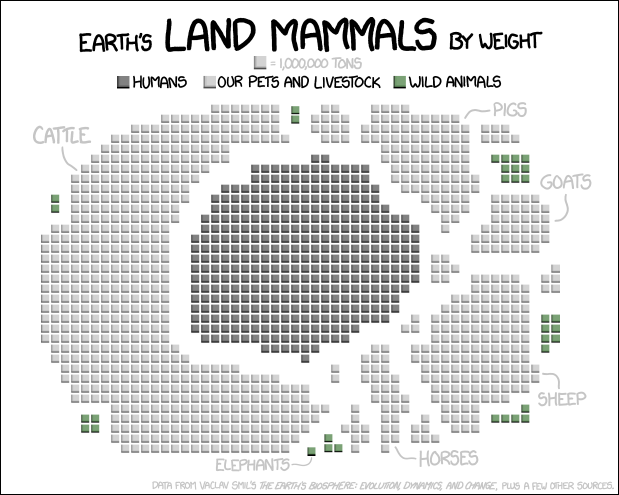

- humans have an effect on our ecology, while we don’t understand it well, most natural effects are non-linear so change can happen very fast

- social norms are rapidly changing

- mobility and interconnectedness is at an all time high

- secularization (the process of religion losing its power and significance in society) continues in the developed world

Summarizing these facts into a consistent narrative is challenging, but I like Thomas Friedman’s way of summarizing the forces changing our culture into three areas. He feels three forces are shaping society: Moore’s law (technology), the Market (globalization), and Nature (climate change and biodiversity loss). He feels all three of these are accelerating and interconnected and impacting the workplace, politics, geopolitics, ethics, and community. Yuval Noah Harari feels that technical disruption and ecological collapse are the two defining forces.

These are helpful ways to organize societal change, but they miss the dimension that matters most to me: morality and the system feeding it. As I traveled in these two cities and saw the geographically diverse but culturally homogenized societal change, I had to ask myself where we are going and if that direction is good or bad for me and the future world my children will inherit.

MAGA anyone? Sorry, not my thing. The burden of every generation is to bemoan the loss of moral clarity of their childhood. It is a good an important question: Am I more concerned with the presence of a moral set of principles or am I holding onto a vision of how society should look based on idealistic remembrances of how things were? Conservatives often fall into this trap. I’m hoping that living and working across the globe physically and studying history mentally helps me burn away the fear-driven pull towards a mythical halcyon past. You have a lot of stuff you can read, if you are reading this you get the perspective of someone in the trenches like you, trying to make sense of all this and trying to be a part of the solution for a better future.

Taking even a mid-term view of history, it clearly isn’t bad. Look at the numbers in the US. Over the past several decades the crime rate has fallen dramatically. The homicide rate has been cut in half since 1991; violent crime and property crime are also way down. And, the future looks good too, Kids are committing less crime so the trend looks like it might continue. Numbers are always a little touchy, but I’d agree that crime is probably a bright spot in our current situation.

Abortion is a key component of our culture and identity wars, but it appears to be declining. Increases in divorce and infidelity could be considered indicators of our moral decay. There’s just one problem: according to the Center for Disease Control and Prevention, the divorce rate is the lowest it has been since the early 1970s. Not only that, but infidelity is down as well.

What about those immoral teens? The teenage pregnancy rate is at its lowest level in 40 years, teen pregnancy rate has plummeted to a third of its modern high. And according to Education Week, the nation’s graduation rate stands at 72 percent, the highest level of high school completion in more than two decades.

Not only is the pregnancy rate lower, but teens are having less sex overall. From 1991 to 2017, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Youth Risk Behavior Survey finds, the percentage of high-school students who’d had intercourse dropped from 54 to 40 percent. In other words, in the space of a generation, sex has gone from something most high-school students have experienced to something most haven’t. Additionally, new cases of HIV are at an all-time low.

The causes of this have more to do with technical disruption than renewed morality. The numbers belie something we see in the public square. The share of Americans who say sex between unmarried adults is not wrong at all is at an all-time high. Grindr and Tinder offer the prospect of casual sex without the pain (or excitement?) of entering the world and learning how to get past the discomfort of discovering if someone is interested in you.

Shame-laden terms like perversion have given way to cheerful-sounding ones like kink. I just read in the Atlantic that Teen Vogue even ran a guide to anal sex; for teens. With the exception of perhaps incest and bestiality—and of course nonconsensual sex more generally—our culture has never been more tolerant of sex in just about every permutation. BDSM plays at the local multiplex—but why bother going? Between prime-time cable and a few clicks, any preference is so instantly available. This is such well known stuff, that I hate to waste your time with such a widely known observation.

There is also no denying, the number of Americans not affiliated with any religion has increased and the number of those attending worship services has declined. And out-of-wedlock births have increased in America so that now at least four in ten children are born to unmarried women. In the United States, church attendance and membership numbers have been in a slow but sure decline since their peak in the 1960s, when about 40 percent went to church every week.

After World War II, there was an international boom in the outward signs of religiosity. People across the West were desperate to return to order. But this boom in religious activity masked deep intellectual, cultural, and political cracks in Christendom. Technology was starting to really change things as well. The rise of the automobile, motion pictures, and television—all accelerated this individualist turn by allowing people to break away from communal experience. This is a trend that social media, modern travel and the mobile phone have accelerated.

Technology also had another important effect. By the late 19th century, Westerners got better at taking the edge off mortality—the physical suffering that, for thousands of years, has driven humans to seek consolation outside material existence. Modern medicine rose in the late 19th and early 20th centuries; for example, take the discovery of germ theory in the 1860s, major advances in vaccines in the 1890s, and Alexander Fleming’s discovery of penicillin in 1928. All these led to a drastic drop in untimely mortality in the West and provided more reason to turn to doctors instead of priests.

Does all this mean that religion falls away as societies modernize? Many feel that religiosity represents incomplete modernity, that the past was more religious than the present, and, as José Casanova has put it, that there is a clear dichotomy between sacred tradition and secular modernity. Casanova describes the three differing and contested meanings of the word secularization: privatization, differentiation, and disenchantment. The Reformation and the Enlightenment presented an individualist turn, which was not itself a turn away from God’s authority. But it did lay the groundwork for a new way of organizing society that, over the centuries, cast religion as a more personal affair and equipped people to live side-by-side with those who disagree or, using Casanova’s terms, to privatize and differentiate.

I tend to focus on privatization as the most causal influence on the current retreat of faith. Søren Kierkegaard is both the father of this turn inward, and a contributor to the evangelical explosion that characterizes a lot of the American religious experience. Kierkegaard focused on the single individual in relation to a known God based on a subjective truth. He fiercely attacked the Danish State Church, which represented Christendom in Denmark. To him, he saw more harm than good with Christianity as a political and social entity. Christendom, in Kierkegaard’s view, made individuals lazy in their religion. I agree that an over-emphasis on the structure of church has the danger of making Christians, that don’t have much of an idea what that word means. Kierkegaard attempted to awaken Christians to the need for unconditional religious commitment.

This strain of thought would result in events as diverse as the the Azusa Street Revival and Second Great Awakening, but it would also lead to less organized religion and centrality of the individual in their faith story. Increasingly, faith is described as a person’s private business, and less a mantle of morality draped over the public square. Some feel this is because we are just too interconnected to have it otherwise. If every person’s worldview is so different from his or her neighbor’s and we work and interact with lots of world views on a daily basis. I agree that privatization is part of the reason religious skepticism and atheism have become not just the quiet views of a few outliers, but socially acceptable positions.

Casanova terms the shift from supernatural to material causes disenchantment. Disenchantment is also a double edged sword. The protestant reformation established a critical tradition that put the individual and sacred scripture in charge: with the responsibility to question everything. This places the emphasis on learning and interpretation and provided the background for radical critique of old models of higher education that led to conditions at University of Tübingen that produced theologians like David Friedrich Strauss. Strauss became famous when he published a book in 1835 called The Life of Jesus, Critically Examined. He said that the rationalists and traditional Christians who believed in the role of the supernatural both got Jesus wrong. The Gospels were not accounts of miracles, nor were they stories of natural events that looked like miracles. It came out to extremely harsh reviews, but I think Strauss has to be seen as a natural consequence of the development of systematic inquiry, or Wissenschaft, which has goal of pushing the boundaries of human knowledge, to question everything, and to get down to the foundations of how and why humans live and think as they do.

Stories like this convince me that no spot in past was a golden age of faith. (Sorry MAGA-fans.) There was either too much structure, with too little understanding, or too much individualism and too little faith overall. Today’s doubt and religious indifference are nothing new. Writing from the Middle Ages is replete with stories of clergy complaining about impiety at all levels of society. Predicting the death of God or institutionalized religion is also not a new pastime. There is a long tradition of prophets proclaiming doom for traditional Christianity.

However, we have the burden of understanding our present time. Before my birth, but very much relevant to my generation was Time’s April 1966 issue. The cover was all black except for giant red letters that asked: Is God Dead?. Time was responding to the growing conversation in Manhattan, London or Toronto about the challenges facing modern theologians who sought to defend traditional religious teachings in a world in which the intellectual elite had come to rely on non-religious sources of authority, like the scientific method and the discoveries happening at modern research universities. Over the centuries since the Reformation, scientists and philosophers had challenged more and more of the church’s traditional claims about everything from human origins to life after death.

Not long after the Time article, there were a series of Supreme Court decisions in the 1960s that prohibited public school officials from requiring Bible reading or prayer in the classroom. Traditional Christian teachings about the role of women in church and at home began to lose their hold. Practices outlawed by traditional Christianity, like abortion and homosexual activity, gained more social acceptance.2

The impact of all this was to undercut an agreed understanding on shared moral framework. I view and judge the health of a society through a moral lens. I feel true strength is moral, the result of the hard choices that define and solidify who someone really is. I feel that there is one best and correct Truth. I agree with Teddy Roosevelt if we have not both strength and virtue we shall fail. Morality is the combination of strength and virtue. In this view, the why matters more than the outcome. If the world economy is improving, but we don’t have roots in a set of principles, unseen dragons are always around the corner.

To understand the dangers in front of us, we don’t have to go farther than the state of modern conservatism. American views of morality are divided between conservatives and progressives. Conservatives are always vigilant for tangible harms that point to our moral decay. For them, and me, any move away from our vision of society is evidence of declining virtue. Progressives, on the other hand, are less concerned with upending the way things were. The philosopher Michael Oakeshott put it best: To be conservative…is to prefer the familiar to the unknown, to prefer the tried to the untried, fact to mystery, the actual to the possible, the limited to the unbounded, the near to the distant. The strength of conservative thought is to acknowledge the authority of family, church, tradition and local associations to control change, and slow it down.

Currently the right is in power in the United States and Britain. However, I’m not sure what this means, since both sides have distanced themselves so much from the values that used to define it. They have occupied the right under a banner of populism and protectionism, with secondary concessions to keep a voting bloc together. Last week, the Economist described that centre-right is being eroded (Germany and Spain), or eviscerated (France and Italy). In other places, like Hungary, with a shorter democratic tradition, the right has gone straight to populism without even trying conservatism.

Despite the key conservative admonition that decimating institutions is among the most dangerous things you can do, the current set of populists are demolishing conservatism itself. The new movement is not an evolution of conservatism, but a rejection of it. Aggrieved and discontented, they are pessimists and reactionaries with scores to settle and grievances to correct.

Classical conservatism is pragmatic and protective of the truth, but the new right is zealous, ideological and the sees truth as theirs to bend. Yes, Trump abuses information to puff up his image, but globally, there is a move away from principled conservatism to a seeking and wielding brazen power without principle with desired dramatic changes. Australia suffers droughts and reef-bleaching seas, but the right has just won an election there under a party whose leader addressed parliament holding a lump of coal like a holy relic. In Italy, Matteo Salvini, leader of the Northern League, has boosted the anti-vaxxer movement. Alternative for Germany has flirted with a referendum on membership of the euro. Were Mr Trump to carry out his threats to leave NATO, it would up-end the balance of power. In the Philippines, Rodrigo Duterte called for the reimposition of capital punishment in the country to execute criminals involved in heinous crimes, such as illegal drug trade, insisting on hanging. He recently asked, Who is this stupid God? when referring to Christians. Vox, a new force in Spain, harks back to the Reconquista, when Christians kicked out the Muslims.

Conservatives traditionally don’t want to break the economy. A no-deal Brexit would be a leap into the unknown, but Tories yearn for it at any economic cost, even if it destroys the union with Scotland and Northern Ireland. Mr Trump and abuses debt to blunt the effect of his trade wars. Brazilians have elected Jair Bolsonaro, who fondly recalls the days of military rule. In Hungary and Poland the right exults in blood-and-soil nationalism, which excludes and discriminates.

Clearly, there are foundational forces at work here. Edmund Burke discovered that institutions provide such as religion, unions and the family provide conservative’s power. Without these institutions to unite society, people outside the cities feel as if they are sneered at by greedy, self-serving urban sophisticates. They were the glue that held together the coalition of foreign-policy hawks, libertarians and cultural and pro-business conservatives.

The problem is with the institutions gone and political power unrooted from any well articulated principles, are the demographics. Conservatives know their voters are white and relatively old. Universities are not producing many more. A survey by Pew last year found that 59% of American millennial voters were Democratic or leaned Democratic; the corresponding share of Republicans was only 32%. Among the silent generation, born in 1928-45, Democrats scored 43% and Republicans 52%. Will enough young people will drift to the right as they age to fill the gap? I doubt it, especially if the right can’t articulate its principles.

The one solution I see is to renew our efforts in two areas: (1) the formation of character and (2) supporting our institutions from a true recognition of their role in society. The first is individual, the second is collective.

Personal Skills

Individuals each need resist the culturally dominant sensibility that translates all of life through the language of individual achievement, freedom, and autonomy and thus dispenses with not just traditional limits to human sexuality, but to limitation more generally.

I wonder about the death of a salesman and the turn towards data and distantness. It is amazing how important soft skills will be distinct in the future.

Collective Institution Strengthening

Amongst other things, this means we need to stop thinking about church in consumer-friendly categories, that we need to devote ourselves to the reading of Scripture and to prayer (and to historic theology!) in order to better see the errors of our own day, and that we should have a strong aversion to commercializing our faith.

What we must recover, then, is the idea of a domain in which we live that is not the global marketplace. We need to return again to the idea of smaller places that we work to build and improve through work characterized first and foremost by affection, intimate knowledge, and patience. This requires a great deal of time from us, of course. (And, for starters, probably means not spending half our weekends on the roads putting on huge, expensive conferences.) This must begin with homes and families, but it can then (slowly) extend outward into neighborhoods, churches, and cities. And, this is key, the work we do in these places must be defined and judged by a standard that is largely indifferent to the braying demands of the market.

So this will almost certainly require significant career sacrifices either in the form of a spouse staying at home to give maximum attention to creating a home or one or both spouses working from home or both. At minimum, it requires a way of thinking about career and work that is largely indifferent toward the corporate ladder, individual achievement, self-realization, and all the other jargony buzzwords that get parroted uncritically by far too many people.

Such a shift will require us to think about duty, responsibility, propriety, and wisdom more than we think about self-advancement, freedom, possibility, and independence.

Footnotes

[^1] One was in the SoHo district of NYC at Piccola Cucina Osteria Siciliana, the other was in the old town of Geneva, Switzerland Au Carnivore

[^2] I feel like I can’t overlook the Scopes Monkey Trial here