AI Agents for Autonomy Engineers

This week I attended a DARPA workshop on the future and dimensions of agentic AI and also caught up with colleagues building flight-critical autonomy. Both communities use the word “autonomy,” but they mean different things. This post distinguishes physical autonomy (embodied systems operating in physics) from agentic AI (LLM-centered software systems operating in digital environments), and maps the design loops and tooling behind each. Full disclosure: I have real hands on experience building physically autonomous systems and am just learning how AI agents work so I’m more wordy in that section and hungry for feedback from actual AI engineers.

The DoW CTO recently consolidated critical technology areas, folding “autonomy” into “AI.” That may make sense at the budget level, but it blurs an important engineering distinction: autonomous physical systems are certified, safety-bounded, closed-loop control systems operating in the real world; agentic AI systems are closed-loop, tool-using software agents operating in digital workflows. For agentic digital systems, performance is the engineer’s goal. Physical systems are constrained by and designed for safety.

Both are feedback systems. The difference is what the loop closes over: physics (sensors → actuators) versus software (APIs → tool outputs). That single difference drives everything else: safety regimes, test strategies, and what failure looks like.

Physical autonomy (embodied AI)

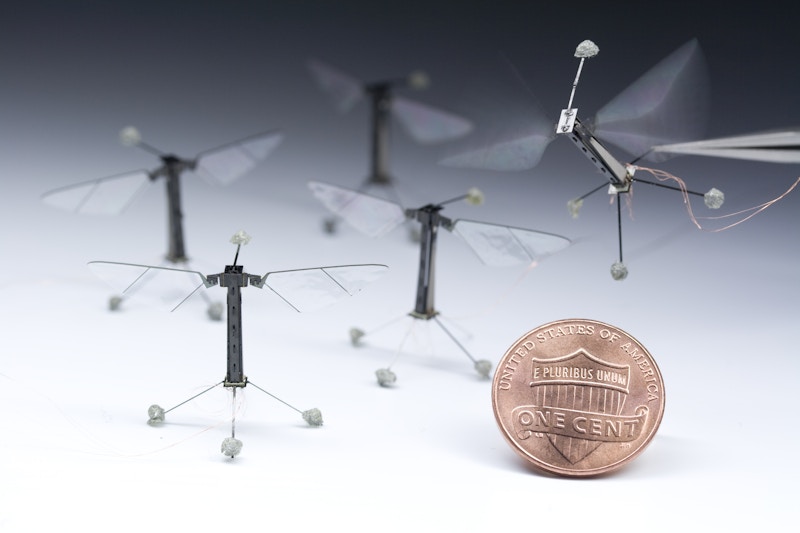

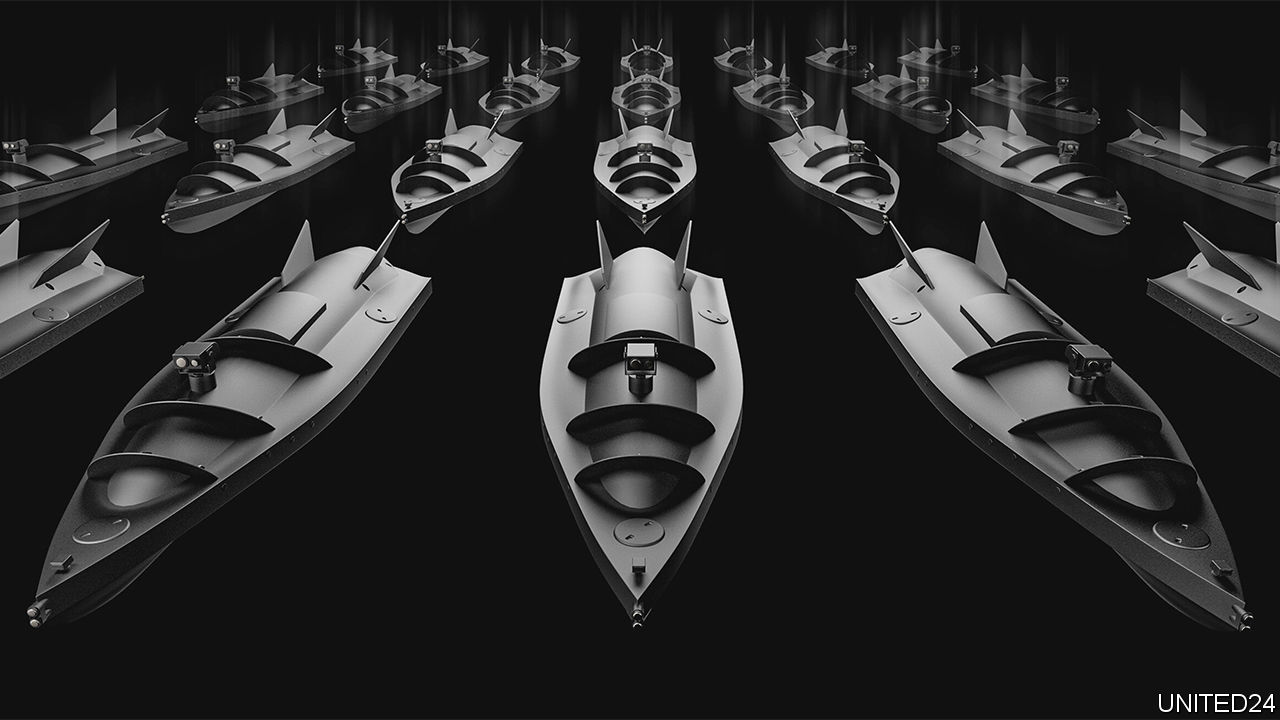

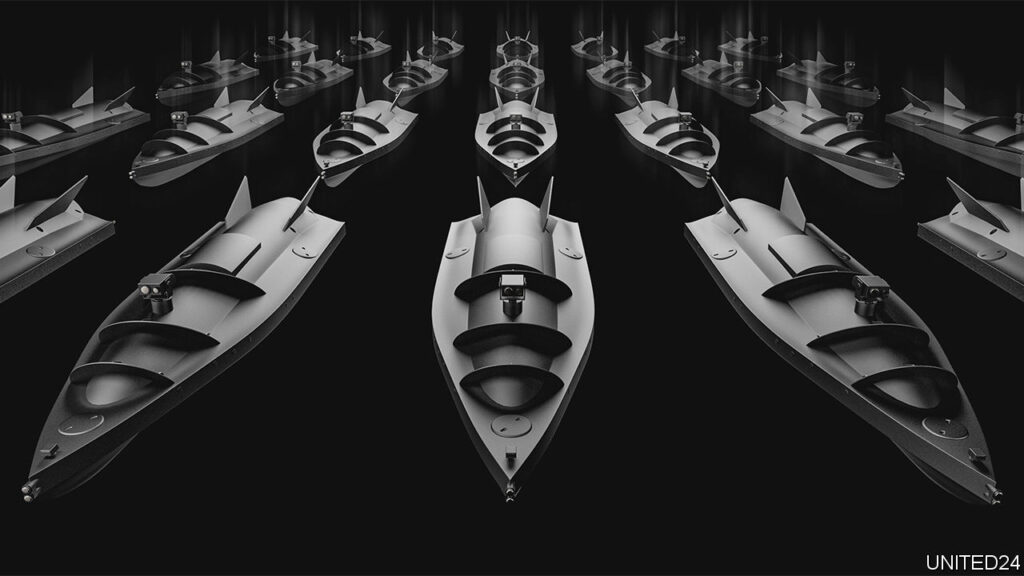

Physical autonomy (often called “physical AI”) is intelligence embedded in robots, drones, vehicles, and other machines with a body. These systems don’t just predict; they act—and the consequences are kinetic. That’s why high-performing autonomy is not enough: the system must be safe under uncertainty.

Conceptually, autonomy is independence of action. Philosophically that’s old; engineering makes it concrete. In physical systems, “getting it wrong” can mean a crash, injury, or property damage—so the loop is designed to be bounded, testable, and auditable.

The physical loop (perceive → plan/control → act → learn)

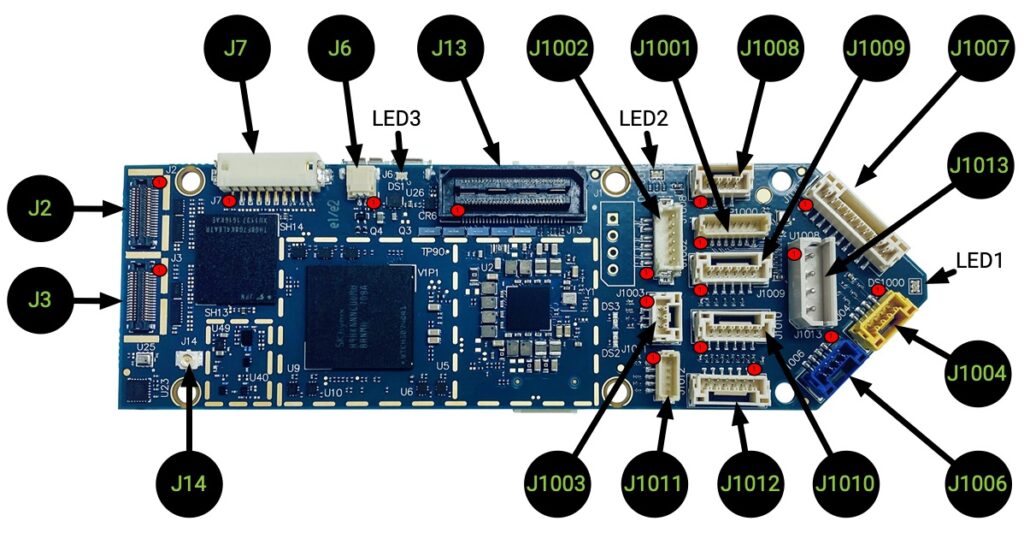

Perceive. Sensors (camera, LiDAR, radar, GNSS/IMU, microphones) turn the world into signals. In practice, teams build low-latency perception pipelines around ROS 2, often with GPU acceleration (e.g., NVIDIA Isaac ROS / NITROS) and video analytics stacks (e.g., NVIDIA DeepStream).

Plan + control. Near safety-critical edges, autonomy still looks modular: perception → state estimation → planning → control. Classical tools remain dominant because they’re inspectable and constraint-aware (e.g., Nav2 for navigation; MPC toolchains like acados + CasADi when explicit constraints matter). Where LLM/VLA models help most today is at the higher level (interpreting goals, proposing constraints, generating motion primitives) while lower-level controllers enforce safety.

Act. Commands become motion through actuators and real-time control. Common building blocks include ros2_control for robot hardware interfaces and PX4 for UAV inner loops. When learned policies are deployed, they’re increasingly wrapped with safety enforcement (e.g., control barrier function “shielding” such as CBF/QP safety filters).

Learn. Physical autonomy improves through data: logs, simulation, and fleet feedback loops. Teams pair real logs with simulation (e.g., Isaac Lab / Isaac Sim) and rely on robust telemetry and replay tooling (e.g., Foxglove) to debug and improve perception and planning. The hard part is that real-world learning is constrained by cost, safety, and hardware availability.

Agentic AI (digital autonomy)

Agentic AI refers to LLM-centered systems that plan and execute multi-step tasks by calling tools, observing results, and re-planning—closing the loop over software workflows rather than physical dynamics.

External definitions help ground the term. The GAO describes AI agents as systems that can operate autonomously to accomplish complex tasks and adjust plans when actions aren’t clearly defined. NVIDIA similarly emphasizes iterative planning and reasoning to solve multi-step problems. In practice, the “agent” is the whole system: model + tools + memory + guardrails + evaluation.

The agent loop (perceive → reason → act → learn)

Perceive. Agents “sense” through connectors: files, web pages, databases, and APIs. Many production stacks use RAG (retrieval-augmented generation) so the agent can look up relevant documents before answering. That typically means embeddings + a vector database (e.g., pgvector/Postgres, Pinecone, Weaviate, Milvus, Qdrant) managed through libraries like LlamaIndex or LangChain.

Reason. This is the “autonomy” part in digital form: the system turns an ambiguous goal into a sequence of checkable steps, chooses a tool for each step, and updates the plan as results arrive. The practical trick is to move planning out of improvisational chat and into something you can debug and replay.

In production, that usually means a few concrete patterns: a planner/executor split (one component proposes a plan, another executes it—often as a planner that emits a structured plan (e.g., JSON steps with success criteria) and a constrained executor that runs one step at a time, enforces policy/permissions, and can reject a bad plan and trigger re-planning), an explicit state object (often JSON) that tracks what’s known, what’s pending, and what changed, and a workflow/graph that defines allowed transitions (including branches, retries, and “ask a human” escalations). Frameworks like LangGraph, Semantic Kernel, AutoGen, and Google ADK are popular largely because they make this structure first-class.

Mechanically, there’s no special parsing logic: the plan is parsed as normal JSON and validated against a schema (and often repaired by re-prompting if it fails). The executor is then a deterministic interpreter (a state machine / graph runner) that maps each step type to an allowed handler/tool, applies guards (required fields, permissions/approvals), and only then performs side effects.

Tooling-wise, the parts that matter most are: structured outputs (JSON schema / typed arguments), validators (e.g., schema checks and business rules), and failure policies (timeouts, backoff, idempotent retries, and fallbacks to a smaller/bigger model). That’s how “reasoning” becomes reproducible behavior instead of a clever one-off response.

Act. This is where an agent stops being “a good answer” and becomes “a system that does work.” Concretely, acting usually means calling an API (create a ticket, update a CRM record), querying a database, executing code, or triggering a workflow. The enabling tech is boring-but-critical: tool definitions with strict inputs/outputs (often JSON Schema or OpenAPI-derived), adapters/connectors to your systems, and a runtime that can execute calls, capture outputs, and feed them back into the loop. Standards like MCP are emerging to describe tools/connectors consistently across ecosystems.

The hard parts show up immediately: (1) tool selection (choosing the right function among many), (2) argument filling (mapping messy intent into typed fields without inventing values), and (3) side effects (a wrong call can email the wrong person, change the wrong record, or spend money). You also have to assume hostile inputs: prompt injection, tool-output “instructions,” and data exfiltration attempts. In practice, tool selection is usually a routing problem: you maintain a tool catalog (names, descriptions, schemas, permissions, cost/latency), retrieve a small candidate set (rules, embeddings, or a dedicated “router” model), then force the model to choose from that set (function calling / constrained output) and verify the choice (allowed tool? required approvals? inputs complete?) before executing. Production stacks handle this with layered defenses: validation and business-rule checks before execution, idempotency keys and backoff for retries, timeouts and circuit breakers for flaky dependencies, least-privilege auth (scoped tokens, service accounts), sandboxing/allow-lists for sensitive actions, explicit approvals for high-impact actions, and end-to-end observability (traces/logs so you can see what tool was called, with what arguments, and what happened).

Learn. Agent systems generate traces: prompts/messages, retrieved context, tool calls + arguments, tool outputs, decisions, and outcomes—stitched together with a trace ID. In production, this typically looks like structured logs + distributed tracing (often via OpenTelemetry), with redaction/PII controls and secure storage so you can share traces with humans without leaking secrets. The payoff is that traces become an eval dataset: you can sample failures, replay runs, and measure behavior (did it pick the right tool, ask for approval, respect policies, and terminate) using tooling such as OpenAI Evals, then iterate on prompts, routers, and (sometimes) fine-tuning.

Implementation patterns (one quick map)

If you’re building agents today, you’ll usually see one of two patterns: (1) graph/workflow orchestration (explicit steps and state; e.g., LangGraph) or (2) multi-agent role orchestration (specialized agents with handoffs; e.g., CrewAI, AutoGen, Semantic Kernel). Google’s ADK, OpenAI’s Agents SDK, and similar toolkits package these patterns with connectors, observability, and evaluation hooks.

Comparing autonomy: physics vs. software loops

| Aspect | Physical autonomy | Agentic AI |

|---|---|---|

| What it operates on | Physics: sensors and actuators in messy environments | Software: APIs, documents, databases, and services |

| Loop constraints | Real-time latency, dynamics, and safety margins | Tool latency, reliability, and permission boundaries |

| Primary failure modes | Unsafe motion, collisions, degraded sensing, hardware faults | Wrong tool/arguments, prompt injection, bad data, silent side effects |

| How you test | Simulation + field testing + certification-style evidence | Evals + traces + sandboxing + staged rollout |

| Oversight | Often human-in-the-loop for safety-critical operations | On-the-loop monitoring with guardrails + approvals for risky actions |

- The loop is the same shape, but the domain changes everything: physics forces safety-bounded control; software forces permissions and security.

- “Autonomy” isn’t a vibe: in both worlds it’s engineered feedback, measurable behavior, and an evidence trail.

- Both converge on systems engineering: interfaces, observability, evaluation, and failure handling matter as much as model quality.

Where they merge (the payoff)

The most interesting systems blend the two: digital agents plan, coordinate, and monitor; embodied systems execute in the real world under strict safety constraints. You can already see this pattern in:

- Robotics operations: agents triage logs, run diagnostics, and propose recovery actions while controllers enforce safety.

- Warehouses and factories: agents schedule work and allocate resources; robots handle motion and manipulation.

- Multi-robot coordination: agent-like planners coordinate tasks; low-level autonomy keeps platforms stable and safe.

Conclusion

Physical autonomy and agentic AI are two different kinds of independence: one closes the loop over physics, the other over software. Treating them as the same “AI” category hides the real engineering work: safety cases and control in the physical world; security, permissions, and eval-driven reliability in the digital world. The future is hybrid systems—but the way you build trust in them still depends on what the loop closes over.